Ilankai Tamil Sangam29th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

The Indo-LTTE War (1987-90)An Anthology, Part 13Ranasinghe Premadasa as the new broomby Sachi Sri Kantha, February 7, 2009

Front Note by Sachi Sri Kantha

That Rajiv was no stranger to political naughtiness and backstabbing has been recorded by Ramasamy Venkataraman (a right-hand man of Indira Gandhi, who was chosen by Rajiv to be his President in 1987), in his presidential memoirs. This was during the three week ascension of MGR’s widow Janaki Ramachandran as the chief minister of Tamilnadu in January 1988. Rajiv fooled Mrs. Ramachandran, a novice in politics, with a promise which he’d flout with ease. To quote Venkataraman:

A few paragraphs later, Venkataraman continued as follows:

Venkataraman’s comment about Janaki Ramachandran’s fluency in Hindi and how Rajiv felt about it, expose something of the difference between Mrs. Ramachandran and MGR. While MGR (pretending a lack of proficiency in either Hindi or English) had tact in keeping his thoughts within himself to keep his political chums and adversaries wrong footed, his wife naively believed that speaking her mind in Hindi would bring benefits to her. And she was taught a bitter lesson in politics by Rajiv. As an aside, I wish to note that a few Indo-philes among Eelam Tamils seem to feel strongly that this Indo-LTTE War Anthology series needs to be stopped or dropped. I don’t see any reason in their censoring logic. Why it should be stopped? Because, it badly hurt the Indian sentiments and rapprochement of Indian mandarins and power prigs in New Delhi towards the cause of Eelam Tamils? Or is it because what happened two decades ago were so nasty and deserves to be hidden? For these Indo-philes, my answer is that, first I’m neither creating nor distorting the events that unfolded between July 1987 and March 1990. If the Indian sentiments are bound to be hurt, let it be; it is time that they learn from their own mistakes. Though I may be tagged as an LTTE-sympathizer, I make no attempt to hide or distort whatever has appeared in these published reports. Secondly, while some of the Indian officers (such as the tweedledum and tweedledee duo B. Raman of the RAW and Col. R. Hariharan of Indian army intelligence, in their current incarnation as gossip vendors to the electronic media) who held positions during this period have been long on offering anti-LTTE gossip to the print and web media, but short on reflecting on their own mistakes and misjudgements. Thirdly, as I have pointed out earlier, what had been served by the Sinhalese historians and non-Sri Lankan commentators in the past 20 years or so, has completely ignored these published sources. As such, I’m following the chronological record of events, as recorded in the then ‘international’ news magazines. Fourthly, the memories and deeds of those who died for the cause of freedom and their beliefs shouldn’t be buried or hidden. Fifthly, much of what appeared in the pre-internet period remains inaccessible to younger generations. In 1989 alone, among the many thousands who died in Sri Lanka, I recognize the following in chronological order: one of my teachers at the Colombo University Prof. Stanley Wijesundara (then the Vice Chancellor of University of Colombo), TULF leaders A. Amirthalingam, and V. Yogeswaran, PLOTE leader Uma Maheswaran, pioneer Tamil industrialist and Sinhalese movie mogul ‘Cinemas’ K. Gunaratnam, University of Jaffna academic Dr. Rajani Thiranagama, and JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera. 1989 also turns out to be the year, when Rajiv Gandhi lost his prime minister’s throne. Currently, the pejorative tag ‘terrorist’ is cavalierly used for propaganda purposes by Sri Lankan officials and media mandarins as meaning the LTTE. The former President Chandrika Kumaratunga was notorious for this cavalier use of the ‘terrorist’ tag in the past, as one who had been personally hurt by terrorists; that she was bombed by LTTE in 1999 and lost an eye (but this version has been rebutted by journalist Victor Ivan, in his book The Queen of Deceit); that her father was killed in 1959 by a terrorist (who happened to be a Sinhalese Buddhist priest Talduwe Somarama Thero), and that her husband was killed in 1988 by the terrorists (who were identified as JVPers). In Sri Lanka (then, as of now), the terrorist can belong to non-LTTE categories as well; including that of the pro-government para-militaries, armed forces vigilantes and Indian intelligence- sponsored assassins. Among the above-noted deaths in 1989, the assassinations of Prof. Stanley Wijesundara and cinema mogul K. Gunaratnam have been attributed to JVP; the assassination of Rohana Wijeweera has been attributed to armed forces vigilantes. Though the LTTE’s hand has been implied and highlighted by the journalists in Colombo and Chennai, evidence for the sponsorship role of Indian intelligence agencies in the killings of Amirthalingam, Yogeswaran, Uma Maheswaran and Rajani Thiranagama have not been negated conclusively by the agencies involved. Another perfidy deserves focus as well. Indian commentators and journalists have attempted to interpret the Indo-LTTE War, in terms of the LTTE’s intransigence to agree to the Rajiv-Jayewardene Accord of 1987. But the fact remains, the same Rajiv-Jayewardene Accord was opposed by the Sinhalese oppositionists (SLFP and JVP in particular), a section of the UNP bigwigs (then Prime Minister Premadasa and the then Minister of National Security Lalith Athulathmudali) and the yellow-robed Buddhist Bhikkus. And the duplicity of India’s own intelligence operatives belonging to RAW in aiding and abetting the JVPers who were agitating against the presence of Indian troops in the island remains an untouched and under-explored theme. Also, the inept pea-brained campaign by the Indian mandarins to train the Tamil National Army (TNA) deserves exposure. As such, I plan to continue this anthology series until the events of March 1990 (that saw the Indian troops leaving the island) have been covered. Presented below, for part 13 of this anthology, are 8 news reports and commentaries that appeared in January-February 1989. These cover (1) the Tamil Nadu state elections held on January 21, 1989, and (2) the Sri Lankan parliamentary election held on Feb. 15, 1989, after a lapse of almost 12 years and dubbed by the Time reporter as “the most violent in Sri Lanka’s already violent history.” For the first time, the parliamentary election was held under the proportional representation system, unlike the previous elections from 1947 to 1977 where the winner was elected on the ‘first to past-the-post’ system. The number of MPs to the parliament was increased to 225. The elections also saw the mauling of the TULF party by the Tamil voters, who had deserted their constituencies under various pretenses since 1983 and came back to contest in 1989. Not only those who represented the TULF, but also those indigenous Tamils (K.W. Devanayagam and C. Rajadurai) who had aligned with the UNP of Junius Jayewardene were also humbled.

A Seasoned Pol Takes Over [Edward W. Desmond, Time, Jan. 2, 1989, p. 75] The streets of Colombo were virtually empty. Armored cars rumbled by and heavily armed members of the elite Special Task Force stood guard outside the pillared town hall. Nonetheless, Ranasinghe Premadasa, Sri Lanka’s President-elect, smiled confidently last week as he stepped with wife Hema from a red Mercedes sedan in front of the building. The result was official: as the candidate of the ruling United National Party, he had won 50.43% of the votes cast in a contest marked by wide-spread violence and a relatively low turnout. In a nationally televised address, Premadasa, 64, hailed the outcome as a major victory. Said he: ‘The ballots of the people have triumphed over the bullets of brutality. We are all relieved that sanity has prevailed over terror.’ Premadasa’s main rival, former Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, 72, the leader of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party, who took 44.9% of the vote, did not share his assessment. The day after Premadasa’s victory proclamation, she lashed out at the President-elect, announcing that she would ask the Supreme Court to overturn the result. Bandaranaike accused UNP members of involvement in the murder of five of her party workers, of stuffing ballot boxes and of other forms of cheating at the polls. Flourishing books of unmarked ballots that she said came from a police station, Bandaranaike declared, ‘State power and wrongful means were used to deprive the majority of the people from freely exercising their right to vote.’ An observation team from the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation demurred, however. The group conceded that the vote may have been ‘flawed’ for some, but contended that the balloting should be ‘viewed positively’. Nonetheless, Sri Lanka’s attempt at peaceful change had started badly. As voters in the nation of 16 million prepared to choose a successor to outgoing President Junius Jayewardene, 82, the country was awash in blood: some 5,000 had died during the previous 17 months. Secessionist Tamil rebels in the north and chauvinist Sinhalese extremists in the south had warned citizens to stay away from the polls on pain of death; not surprisingly, only half of the 9.37 million registered voters showed up to cast ballots. Some election officials had to be rounded up by police and taken to polling stations under armed guard. Eighteen civilians – including two polling officials – and three members of the security forces were murdered on election day. In the south, members of the People’s Liberation Front (JVP), a militant Sinhalese group that seeks to overthrow the government, felled trees across roads, pounded nails into pavements to damage auto tires, and pulled down telephone wires and poles in a bid to foil the balloting. In the southern village of Yatiyana, the tactics worked well: soldiers finally managed to escort polling officials to their posts by 9 am, two hours after voting was slated to begin, but when the polls closed, only twelve of 2,586 registered voters had cast their ballots. The JVP’s threat of violence was the principal force that kept people away. Said one sarong-clad elder: ‘I wish the army would come and force us to vote. That way we would have an excuse for the JVP.’ In some areas, security forces did just that, half-cajoling, half-threatening voters to do their civic duty. Premadasa will be sworn in as President on Jan. 2. The stolid politician, who has served as Jayewardene’s Prime Minister since 1978, is something of an exception in Sri Lankan politics: a man of the people. Both Jayewardene and Bandaranaike come from wealthy, upper-caste families that consider politics something of a feudal responsibility. Premadasa, a devout Buddhist, hails from a lowlier background. His hardworking parents – his father owned a fleet of rickshas – made sure he attended good local schools, but the President-elect never attended a university. Instead, he entered politics as a union organizer; a skillful orator, he eventually built a political machine in the working-class district of central Colombo. Before being selected as Prime Minister, Premadasa twice held the position of Minister of Local Government. Western diplomats in Colombo compare Premadasa’s rise from modest beginnings to that of Britain’s Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and his political instincts to those of New York City’s 19th century Tammany Hall bosses. Says one of Premadasa’s wealthy backers: ‘You perform or you get out.’ Detractors charge that he is authoritarian in his methods, but admit he is hard worker. As Prime Minister, Premadasa appeared in his office by 4.30 every morning and stayed in touch with the citizenry at ceremonies commemorating his achievements, such as those marking progress in an eleven-year-old effort to build 1 million housing units for the poor by the end of 1988. The challenge ahead is formidable. The President-elect opposes the July 1987 accord between his predecessor and Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, that brought some 70,000 Indian peacekeeping troops to the island. The soldiers have since found themselves battling the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in the north. The Sri Lankan army, meantime, is struggling with the JVP, which gained strength from what many Sri Lankans see as an Indian infringement on national sovereignty. The victorious Premadasa must now lead his party in parliamentary elections scheduled to take place on Feb.15. Following his triumph last week, the President-elect asked the JVP to rejoin the democratic process, but also warned that violence ‘must and will end.’ He did not predict when. ***** Now Comes the Hard Part [Anonymous, Asiaweek, Jan. 6, 1989, pp. 24-25.] Choosing who should lead the nation was hard enough. But many of Sri Lanka’s 9.4 million eligible voters also had to wrestle with a life-and-death decision during the country’s Dec. 19 presidential election: whether to show up at the polling stations at all. Both the militant Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front), a Sinhalese chauvinist group, and Tamil extremists had threatened to kill those who dared to vote. Government security forces, on the other hand, said boycotters would be considered enemies of the state. In the end, about 55% cast ballots, considerably lower than the 81% turnout in the first-ever presidential race six years ago, but impressive enough under the circumstances. Along with democracy, the winner was Ranasinghe Premadasa, candidate of the ruling United National Party, Prime Minister in the last government, Premadasa received 2.56 million votes, 50.4% of the total cast. It was just enough to satisfy the Constitution, which requires a majority mandate. Sirimavo Bandaranaike of the opposition Sri Lanka Freedom Party, who threatened to go to the Supreme Court to protest Premadasa’s win, was credited with 2.28 million votes, 44.9% of the total. Oswin Abeygunasekara of the Sri Lanka Mahajana Pakshaya (People’s Party) trailed with 4.6%. ‘The ballots of the people have triumphed over the bullets of brutality,’ declared the 64-year-old president-elect. But it was a bloody victory. At least 30 people were gunned down on election day, half of them while queuing at the booths. That brought the number of lost lives to more than 400 since the election was announced on Oct. 10. Most of the killings were blamed on the JVP. They were bitterly opposed to the 1987 Indo-Lankan peace accord, under which an Indian peacekeeping force was sent to Sri Lanka to put down Tamils fighting for a separate homeland in the north. Premadasa, scheduled to take over from President Junius Jayewardene on Jan. 2, faces a daunting task. His most immediate concern is restoring law and order. A state of emergency, in force since 1983 to fight Tamil rebels, has recently been turned against the JVP terrorists. The security forces’ wide-ranging powers include the right to shoot terrorists on sight and to dispose of the bodies without an inquest. This has led to charges that numerous people have been summarily executed on mere suspicion of being JVP sympathizers. That will become academic after Jan. 15. Under the Constitution, Parliament can only extend a state of emergency on a month-to-month basis. President Jayewardene dissolved the assembly on Dec. 20 to pave the way for general elections, a key demand of the political opposition. Admits National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali: ‘We don’t want to get into a situation where we have to resummon [the dissolved] Parliament.’ The president-elect is instead extending the olive branch. In his victory speech, he called on ‘those who still have to join the democratic process,’ an apparent reference to the Sinhalese terrorists, to participate in the Feb. 15 parliamentary elections. ‘I am available for any consultation with a view to arriving at a practicable solution,’ he added. Some political analysts believe the JVP may now be more amenable to returning to the mainstream in the light of its failure to stop the polls. Much would depend, however, on Premadasa’s success in negotiating the departure of the Indian troops. In the hustings, Premadasa had been vocal about his opposition to Indian forces on Sri Lankan soil. He has promised to work for a troop withdrawal and renegotiate the pact with India. New Delhi has been conciliatory. ‘The government looks forward to working in close cooperation with the new president to further improve the close relations between India and Sri Lanka,’ said India’s external affairs ministry. But political considerations complicate the issue. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi will want to keep on the right side of his country’s 55 million Tamils, whose concern for their brethren in Sri Lanka led Gandhi to push for the 1987 pact. Legislative assembly elections are scheduled in the southern state of Tamil Nadu on Jan. 21 and general elections are due in late 1989. And the Tamil problem in Sri Lanka must also be factored in. Elections were recently held in the Northern and Eastern provinces, where most Tamils live. The provinces are guaranteed limited autonomy by the peace pact, but many armed groups, particularly the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, still hold out for complete independence. Without the Indian contingent, the guerillas may go on another violent spree. If Premadasa fails to placate the JVP, the Sri Lankan military will be hard put to wage war on two fronts. There are also questions about Premadasa’s mandate to lead the country. In areas where most Sri Lankan Tamils live, voters generally stayed home. In Jaffna district in Northern Province, only 22% of eligible voters cast ballots. Of these, just 28% voted for Premadasa. In JVP strongholds in Southern and North Central provinces, turnout was equally poor. Bandaranaike carried the Sinhalese votes in both provinces. In parts of the country where voter turnout was heavy, mostly in the urban areas, Premadasa nosed out Bandaranaike, but in many cases only slightly. In Colombo, the capital, the ruling party candidate won 49% while Bandaranaike had 46%. With the margin of victory so narrow, ex-PM Bandaranaike has refused to accept defeat. ‘My lawyers have advised me that there is adequate evidence and information to have the election of the UNP candidate declared null and void,’ she said. A ten-member observer group from neighbouring countries did receive complaints of irregularities. But its interim report concluded that ‘the electoral process, even though it may have been flawed in the perception of some…should be viewed positively.’ Can Premadasa deliver? As prime minister for the past ten years, he can claim to know his country’s problems intimately. He has carefully cultivated an image as a ‘servant of the poor’ and a defender of ethnic and religious minorities, which supporters say figured prominently in his win. His well-known stand on the Indian presence is in accord with popular sentiment. But there the shortlist of advantage ends. On the other side of the ledger is the deep-seated anger brought on by years of communal strife. The president-elect will need all his political skills to overcome that legacy of hatred. ***** Sri Lanka: ‘In 15 days we had to perform 15 amputations’ [Marguerite Johnson; Time, January 9, 1989, p. 44.]

Anywhere else, the Medecins sans Frontieres team might be mistaken for tourists. The three men are clad in jeans, the lone woman in a khaki skirt; medical bags swing casually from their shoulders. But in Point Pedro, in the battle-scarred northern tip of Sri Lanka’s Jaffna peninsula, foreigners have been rare visitors in the five years since Tamil guerrillas began their insurgency for a separate state. Far from sightseeing, the MSF team – one surgeon, two anesthesiologists and a nurse – is on a difficult and often dangerous mission of mercy.

For a populace of 200,000, Point Pedro has only one hospital. At any given time, between 50 and 60 of the 210 beds are occupied by people needing surgery. The team performs about 150 operations a month in Point Pedro and one day a week heads for Tellippalai hospital, nine miles away, where it handles another 80 or so surgeries. Says Menciere: ‘We are on duty 24 hours of the day.’ Medications, for which the team has to rely on the Sri Lankan government, are always in short supply; water and electrical power are erratic. The most harrowing period for the group followed the signing of the Indo-Sri Lankan accord in mid-1987, when many Tamils who had fled the fighting returned to their homes to find that the guerrillas had set booby traps in them for Sri Lankan soldiers. The mined houses exploded when residents stepped inside. ‘In 15 days,’ recalls Menciere, ‘we had to perform 15 amputations, most of them on little children and old women.’ Mines still pose a constant peril. A few weeks ago, the team had to remove the leg of a seven year-old who had stepped on a mine.’ ‘I was really sad that day,’ says Dominique Laulan, 33, a French nurse. Despite a 7 pm curfew and the lack of television and telephone, the medics have no complaints about living conditions. They spend their leisure time listening to music, playing cards or reading. When possible, they go for a late afternoon swim before making their final rounds of the surgical wards. But they are pessimistic about an early end to the Tamil conflict and expect that MSF will be needed for several years to come. ‘I will return,’ promises Menciere. But first there will be a brief respite in France and a probable third tour in Afghanistan. ***** Premadasa Takes Over [Marguerite Johnson; Time, Jan. 16, 1989, p. 17] In a solemn and elaborate ceremony, Ranasinghe Premadasa, Sri Lanka’s new President, was sworn into office last week at the Temple of the Tooth, the most sacred Buddhist shrine in Kandy, 72 miles north-east of the capital of Colombo. After monks chanted prayers, Premadasa presented the shrine with a baby elephant and 25 acres of land. In an address to the nation from the temple balcony, he also offered another gift of sorts: withdrawal of 3,000 of India’s 70,000 peacekeeping troops stationed in the Northeastern province. Pledged Premadasa: ‘We should not and will not create situations that provoke or invite intervention.’ The withdrawal was little more than a token gesture, but nonetheless was politically significant for Premadasa. The presence of Indian soldiers, dispatched under the 1987 India-Sri Lanka accord between Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Junius Jayewardene, then Sri Lanka’s President, was a key issue in last month’s presidential elections. Under the pact, Sri Lanka agreed to grant limited autonomy to its Tamil minority, while India undertook to disarm separatist Tamil guerrillas, mainly those belonging to the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. That operation proved to be bloodier and far more difficult than either country had anticipated. Moreover, it served to reactivate a Sinhalese extremist organization, the People’s Liberation Front (JVP), which over the past 18 months has killed hundreds of government employees and supporters of the accord. In all, post-agreement violence has claimed the lives of more than 5,100 Sri Lankans and 700 Indian soldiers. To redeem his campaign pledge to send the Indian peacekeepers home, Premadasa asked New Delhi last month to consider a phased pullout. On Jan. 1, following a meeting between Jayewardene and Gandhi at the South Asian summit in Islamabad, the Indian government announced that two battalions were being withdrawn in view of Sri Lanka’s ‘encouraging progress’ in carrying out the terms of the 1987 accord. That pullout should strengthen the new President’s position and enhance the prospects of his United National Party in parliamentary elections, scheduled for Feb. 15. UNP members hope that the initial pullout will be the beginning of a sustained withdrawal of the remaining Indian troops. At the same time, however, Premadasa realizes that he still needs an Indian military presence, since all of Sri Lanka’s forces have been deployed against the JVP in the south. Although army headquarters in Colombo has stopped announcing a daily death toll, there are reliable reports that the JVP and anti-JVP death squads are killing an average of ten people a day. In Tamil areas, moreover, it is the Indian peacekeeping forces that have been instrumental in confining the militarily weakened Tigers to the jungles. Says Lieut. General Hamilton Wanasinghe, the Sri Lankan army commander: ‘We simply do not have the numbers to tackle the security situation all over the country.’ The forthcoming parliamentary elections will require unprecedented security arrangements to protect the 9 million voters and 1,393 candidates. With both the JVP and the Tigers boycotting the balloting and threatening to cause more trouble, Premadasa may be relieved that India’s withdrawal thus far has been little more than symbolic. [reported by Anita Pratap/ New Delhi]. ***** Southern Setback for Rajiv [Anonymous; Asiaweek, Feb.3, 1989, pp. 22-23] As Muthuvel Karunanidhi’s motorcade arrived at his party’s headquarters in Madras, the thousands packing the compound raised their hands in salute. Men, women and children jostled to be near their thalaivar (leader) at his hour of triumph. Red-uniformed guards tried to keep the crowd under control. As Karunanidhi, wearing dark glasses to hid a squint, stood on his campaign van, they shouted: ‘Long live the leader of Dravida [South Indian] self-respect!’. When the frenzied cheering would not stop, the man whom his supporters call Kalaignar (Learned One) pleaded, ‘If we celebrate this victory with dignity and calm, we will be able to win over all the Tamils.’ But the new chief minister of the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu could not resist proclaiming the significance of his victory and taking a dig at the Indian prime minister: ‘The vote was against Rajiv.’ Indeed, for Rajiv Gandhi and his ruling Congress (I) party, the results of the Jan. 21 state elections in Tamil Nadu were a wrenching disappointment. Receiving Vietnamese Communist Party chief Nguyen Van Linh in Delhi last week, Gandhi steered his guest away from reporters and refused to answer questions. The prime minister had taken a personal interest in the campaign, making at least ten trips covering all the state’s districts. He attracted large crowds, but could not pull in the votes on election day – Congress (I) came in third with only 26 out of 234 seats in the state assembly. A good result would have encouraged Gandhi to call early general elections, which are due by the end of the year. For Karunanidhi, 64, whose Dravida Munnetra Kazagham (DMK) party grabbed a two-thirds majority in the legislature, victory was sweet revenge. The film scriptwriter and veteran politician had been chief minister before, but was dismissed in 1976 by then prime minister Indira Gandhi, Rajiv’s mother. By winning back power he not only thwarted the premier, but finally upstaged bitter political adversary and film star Maruthur Gopalamenon Ramachandran, popularly known as MGR. Ramachandran, who died in December 1987, was a legendary screen hero, adored by millions and instantly recognizable by his trademark fur cap and dark glasses. He formed the All-India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazagham (AIADMK) in 1972 after breaking away from Karunanidhi’s party. Winning a landslide victory in 1977, MGR relegated his rival to the role of opposition for the next ten years. At his death his party was carved in two by his widow, V.N. Janaki, and his political protégé, actress Jayalalitha Jayaram (see, below). Janaki had been appointed to succeed her husband as chief minister on Jan.3, 1988. But before the month was out fierce fighting erupted on the assembly floor during a vote of confidence on the new government. After the incident, Gandhi sacked the three week-old administration and placed Tamil Nadu under president’s rule. The recent elections were the first since then. Never before had a state election campaign been so boisterous and colourful. Larger-than-life portraits of party leaders stared down from city walls. For hours people lined streets to hear candidates – many of them film stars – plead for votes. Loudspeakers incessantly blared political rhetoric. Yet through the din and glitter, the 35 million electorate sent out an unmistakable message – the Tamils wanted a strong, regional party to govern them. The DMK was the clear favourite in both urban and rural areas. Voters seemed to ignore glamour, opting instead for candidates who had links to their constituencies. Although his popularity rivaled MGR’s, actor Sivaji Ganesan lost to his DMK opponent by a huge margin of 10,000 votes. Of the major parties, the DMK had the shortest and most specific program. Although the party was originally built on anti-Hindi, Tamil chauvinism, this has changed over time. Among the DMK’s supporters was Haryana chief minister Devi Lal, who refuses to speak anything but Hindi. Yet Karunanidhi claimed the victory was a complete rejection of Gandhi’s ‘anti-Dravidian stance and his attempt to denigrate and obliterate the Dravidian sentiment.’ By race, the people of Tamil Nadu are Dravidians, and Tamil is a Dravidian language. Karunanidhi, however, benefited from the split in the AIADMK and from the strong backing he received from the national opposition National Front. Jayalalitha’s faction took the second largest number of seats, while Janaki’s could win only one. Despite his boasts at Gandhi’s expense, Karunanidhi adopted a conciliatory tone after his victory. ‘I know that some people have talked ill of us, carried on a campaign of calumny against us and some have stabbed us in the back,’ he said. ‘But we should not be vindictive.’ Still, bumpy times may lie ahead in relations between Delhi and Madras. Sri Lanka is likely to be the chief obstacle. Asked if he would call for the complete withdrawal of Indian forces from the island nation, Karunanidhi replied cautiously: ‘We would like to study how the governments have so far tackled the problem and come to a decision.’ But he warned that his government ‘would continue to struggle for a just, peaceful and durable solution to the problems of the people of Tamil Eelam.’ Karunanidhi also hinted that separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam leader Velupillai Prabhakaran supported him. ‘He believes that the DMK will help him find a peaceful and just settlement of the Tamil question,’ he claimed. During the year of Delhi’s rule, Gandhi had hoped the free rein he had given Governor P.C. Alexander to clean up Tamil Nadu’s paralysed administration would pay dividends at the polls. The failure of Congress (I) to win the state means the party controls no major southern state and remains limited to its northern Indian base. But Gandhi could find some consolation in the results of the elections held the same day as the Tamil Nadu polls in the small northeast states of Nagaland and Mizoram. Congress (I) captured majorities in both state assemblies. Gandhi’s setback in the south, however, was compounded by a scandal in Madhya Pradesh. The Congress (I) leadership in the central state ousted Chief Minister Arjun Singh after he had been accused of misappropriating charity funds to pay for the construction of a mansion in the capital Bhopal. The ruling party’s poor showing in Tamil Nadu has been a shot in the arm for Gandhi’s opposition – further evidence that the nation is looking for a change, they argue. ‘It is a total rejection of Mr. Gandhi’s misrule and heralds the beginning of a new politics in the country,’ said Janata leader M.S. Gurupadaswamy. Added S.R. Bommai, chief minister in Karnataka: ‘It is also a message for the opposition parties to consolidate themselves to go to the people with alternative programs and policies.’ Rivalries: Star Wars Politics in Tamil Nadu, the film capital of southern India, could well be the subject of a movie. Every major party in the Jan. 21 state election had a former or current film star in the running or campaigning. The man who led the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) party to victory, veteran politician Muthuvel Karunanidhi, is also a well-known writer of fiery screenplays. The election results could not have turned out better for him if he had written the script himself. Karunanidhi takes over the lead role from a man who perfected the art of political drama, monumental screen star Maruthur Gopalamenon Ramachandran. Chief minister of Tamil Nadu for over a decade, MGR left a gaping hole in the state’s politics when he died of a heart attack in December 1987. Barely a month after he was buried, members of his All-India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) took separate cues. The party split into two factions, led by its leading ladies – grieving widow V.N. Janaki and the ‘other woman’, buxom and ivory-skinned actress-politician Jayalalitha Jayaram. Both were vying for the role of chief minister. Janaki, 63, one of MGR’s early co-stars, had left her husband to marry the movie hero. In last week’s elections, she contested MGR’s old Andipatti constituency, never failing to remind voters she was his widow. ‘MGR’s work should not die with him,’ she told them, pleading for a chance ‘to finish what he had started.’ The electorate was not convinced, however; she came in third behind winner P. Asaiyan of the DMK. The convent-educated and urbane Jayalalitha, 40, was an aggressive campaigner. An MP and AIADMK propaganda secretary, she was rumoured to have been romantically linked with MGR, her political mentor. During the campaign she often recounted how Janaki barred her from entering MGR’s residence after the chief minister’s death, and how, at the funeral, Janaki’s nephew kicked her off the cortege. ‘I have no one to care for me except you,’ she declared at campaign rallies. ‘I have been orphaned by MGR’s death. You must protect me now.’ Janaki persuaded film star Nirmala to stand against Jayalalitha. Nirmala and Jayalalitha had debuted together in a 1965 MGR movie. Janaki’s recruit said she was running to repay MGR for helping her out after she went into debt in the mid-1970s when her film venture turned sour. Jayalalitha, however, defeated the politically inexperienced Nirmala, who could not even win enough votes to recover her election deposit. Other parties also recruited from the movies. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s ruling Congress (I) signed up popular Hindi screen idol Sri Devi to campaign for her father, who was beaten badly by the DMK candidate. Karunanidhi managed to get screen villain M. R. Radha, a bitter adversary of MGR, to lure his daughter, the sultry Radhika, away from the set to campaign for the DMK. ‘I am only here for my father,’ she told Asiaweek. ‘I have call sheets for the next two years.’ [Note by Sachi: The sentence that “Nirmala and Jayalalitha had debuted together in a 1965 MGR movie.” is in error. The movie they debuted, Vennira Aadai was made by director C.V. Sridhar and MGR didn’t star in it. The suggested reason for why Jayalalitha was kicked off the cortege of MGR, was because in haste she had climbed the cortege with her sandals, which was considered as a discourtesy.] ***** Whose Revolution Will It Be? [Sri Lanka’s Special Correspondent; Economist, Feb.11, 1989, pp. 26 & 28] ‘Please write something nice about us,’ says a government official weary of Sri Lanka’s woeful reputation for self-destruction. Very well. The shops and banks are open, the buses and trains are running again, there is petrol in the pumps, the curfew has been lifted. Many in Sri Lanka, where ‘auspicious days’ decide the movements of people from the president downwards, attribute the present relaxed mood to an unusually favourable arrangement of the planets. An earthier view is that Sri Lanka seems to be pausing for breath between its presidential election of last December and the parliamentary election due on February 15th. Perhaps, the optimists are saying, Sri Lanka’s troubles can at last be settled by talk instead of violence. This optimism manages to survive a daily battering as some new atrocity is reported. The most dangerous occupation in Sri Lanka is that of parliamentary candidate. By the middle of this week 12 of them had been shot dead and many of their supporters had died in the crossfire. These murders, however, appear to be mainly the result of personal animosities and party rivalries rather than the work of terrorist groups, although it has sometimes been expedient to blame the terrorists. The Tamil Tigers and the JVP (Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, or People’s Liberation Front), the two main groups that believe the way to a better future is to kill people, are lying low. This is of little comfort to be bereaved, but it cheers up everyone else. If only the Tigers and the JVP can be persuaded to keep quiet, business will boom, the universities will reopen and the tourists will return, lured once again by travel articles about sun-kissed beaches and the ancient frescoes of bare-breasted ladies at Sigiriya. ‘The tears of grief will turn to tears of happiness,’ says President Ranasinghe Premadasa. Yes, it is easy to get carried away. The reality is that Sri Lanka has a range of mind-splitting problems. It has the now famous problem of the Tamils who want a separate state in the island; the problem of the majority Sinhalese who have come to hate the Tamils; and the problem of what to do about the 45,000 Indian soldiers whose presence in Sri Lanka is resented by Tamils and Sinhalese alike. Many Sri Lankans, probably most, blame India for all their troubles. From the early 1980s India supported the Tamil independence movement and allowed Tamil guerrillas to train in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. In 1987 India persuaded the Sri Lankan government to grant the Tamils limited self-rule in the north-east. Indian soldiers were allowed in as a ‘peace-keeping force’ but were soon fighting those Tamils who continued to demand an independent state. An anti-Indian movement sprang up in the Sinhalese south. Its most violent expression is the JVP. Call it the Jolly Vicious Party, says a Sri Lankan with a taste for black humour. In little over a year it has killed more than 700 supporters of the government. Their offence, the JVP says, was that they allowed India, a traditional enemy, to invade Sri Lanka. Get rid of the Indian soldiers then? If they go, the Tigers, a subdued but far from beaten force, will come out of the jungle and resume their fight for the state they call Tamil Eelam. The Sri Lankan army is not reckoned strong enough to replace the Indians. Mr Premadasa says the Indians will go but has not said when. Although he was prime minister in the government of the previous president, Mr Junius Jayewardene, he has managed to distance himself from the deal that Mr Jayewardene did with India. The JVP, which tried to kill Mr Jayewardene, has spoken approvingly of Mr Premadasa. The Sinhalese guerrillas claim they helped him to power. Their threat to kill voters prevented the high poll that would have helped the main opposition candidate, Mrs Sirimavo Bandaranaike, whose government put down a JVP uprising in 1971. In the JVP view, Mr Premadasa will prove to be a weak president unable to cope with the revolution it judges is close. When he falls, the small group of well-educated and ruthless young people who control the JVP believes it will take over the country. Nonsense – maybe. Mr Premadasa’s supporters claim he is strong, even ruthless. They note that during the presidential campaign he cruelly cold-shouldered Mr Jayewardene, his former mentor, in order to demonstrate that he is his own man. But Mr Premadasa’s own thinking coincides with the JVP’s on one point: he believes that unrest starts with poverty. He plans a revolution of his own. He is promising more than 1.4m poor families a gift of 2,500 rupees ($80) a month for two years. This is a lot of money in Sri Lanka. A factory worker in a free-trade zone gets 1,000 rupees a month. Each year, this handout would equal at least half and possibly all of the government’s present yearly revenues, depending on how the largesse was distributed (under one plan part of it could not be drawn until the end of the two-year period). The president’s advisers propose less apocalyptic ways of helping the poor, but he appears to be unshiftable. He recalls that he grew up in a poor family to whom a lump sum such as this would have been salvation, the means to start a small business. That is what he is promising his people. If necessary he will simply print the money. Economics is not Mr Premadasa’s strong suit. The International Monetary Fund is already frowning. The second instalment of a loan agreed to last year is due to be given to Sri Lanka in March. If this is withheld it will cast a cloud over an aid meeting in June arranged by the World Bank. Under the Jayewardene government the country became self-sufficient in rice and substantially increased its export earnings, mainly from textiles and tea. But Sri Lanka still has to count on the generous charity of overseas friends. The former finance minister, Mr Ronnie de Mel, who fell out with Mr Jayewardene last year, was the wizard who kept the aid flowing in. Mr de Mel, who (unlike the new president) is economically literate, might have been able to persuade Mr Premadasa of the vices of his plans. If not, even he would have found it impossible to persuade donors to keep writing cheques. The paper kites are flying cheerfully over the green on Colombo’s seafront. The splendid Buddhist temple in Kandy has a new roof of gold. It is not difficult to find pleasant things to say about Sri Lanka. Alas, they are mostly superficial ones. ***** Mathematics for Beginners [Anonymous; Economist, Feb.25, 1989, pp. 32 & 34] Here is an interesting problem in simple arithmetic. The Sri Lankan government’s projected expenditure for the 1989 financial year, which begins in April, is 122 billion rupees ($3.7 billion). Estimated revenue is about 50 billion rupees. That leaves 72 billion rupees to be found from new taxation, domestic borrowing and foreign aid. The best guess is that perhaps 32 billion rupees can be raised in this way. So 40 billion rupees – a full third of the budget – is still unaccounted for. This arithmetic is the despair of the people trying to draft the budget, which is to be presented to parliament in March. Their labours would be much easier if they could ditch an expensive election pledge made by the new president, Mr Ranasinghe Premadasa. He promised more than 1.4m poor families a gift of 2,500 rupees a month for two years. However much this 42 billion-rupee-a year handout is fudged – for example by keeping of it back as enforced ‘savings’ - it still amounts to a big lump of the budget. Mr Premadasa, seems determined to honour his promise, even if he has to print a lot of worthless money to do it. His obstinacy is reckless, but he has his reasons. The promise may have been the deciding factor in the parliamentary election of February 15th, which was won by his United National Party. In the December presidential election Mr Premadasa barely scraped home against the main opposition candidate, Mrs Sirimavo Bandaranaike. He fought last week’s election with renewed determination. His party won 125 of the 225 seats: not enough to give it the two-thirds majority it had hoped for to make constitutional changes, but pretty good. Mr Premadasa’s administration will, he says, have a distinctive moral and religious tone. He has created a new cabinet job, for Buddhist affairs, which he has kept for himself. His opponents are not prepared to give the government absolution. There has been widespread dissatisfaction that the previous president, Mr Junius Jayewardene, brought in the Indian army to tame the Tamil Tiger guerrillas who are rebelling in the north-east of the island. About 5,000 of the Indians are said to have left, but what about the 45,000 who remain? The opposition also complains that under both President Premadasa and his predecessor the security forces have got away with arresting and murdering civilians in their hunt for members of the violently anti-Tamil and anti-Indian People’s Liberation Front. The opposition in the new parliament will be far more vociferous than the fag-end of politicians who argued against the five-sixths majority of the ruling party in the last one. The Sri Lanka Freedom Party, which had eight seats in the previous parliament, now has 67. Still, it will take time for it to recover its morale after its defeats in both these elections. Mrs Bandaranaike is already under pressure to step down as leader. She will be nearly 79 by the time of the next presidential election in 1995. The biggest surprise of the general election was that an independent group, contesting the north and east, became the third largest party in the new parliament. It won 13 seats in what was interpreted as an indirect vote of confidence in the Tigers, the only Tamil militant group still fighting for a separate state. The party was supported by the Eelam Revolutionary Organisation of Students, which is closely associated with the Tigers. It won eight of the 11 seats in the Jaffna peninsula, the Tigers’ former stronghold. The Tigers, who had been seriously weakened by the 16-month offensive of the Indian peacekeeping force and by the successful holding of local elections in the east of the country last November, will feel duly encouraged. No end to the violence in this little country is in prospect. Unless Mr Premadasa’s budget is the beneficiary of a miracle, prices look like running riot. The president is going to need all the comfort he can get from his ministry of Buddhism. ***** More Voting, More Dying [Lisa Beyer; Time, Feb.27, 1989, p. 17.] It was a high price to pay for casting a ballot. H. Tillekeratne, a retired government official, had just voted and was bicycling home from a local polling station south of the capital of Colombo when a sniper’s bullet ripped through his head. He thus became one of 57 Sri Lankans killed on election day for daring to defy a balloting boycott called by two extremist groups: 125 others were injured. Despite an unprecedented show of force by 41,000 government security personnel deployed to protect voters, last week’s parliamentary election was the most violent in Sri Lanka’s already violent history.

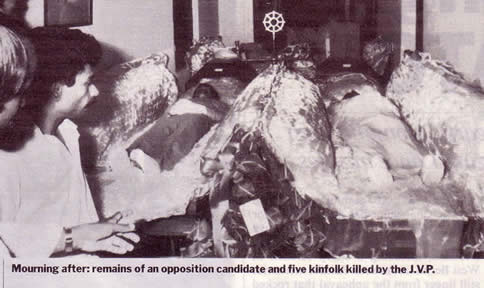

The carnage on election day was just the finale. In the bloody five-week campaign, nearly 1,000 people, including 13 candidates , were slaughtered. The main source of violence was the militant People’s Liberation Front (JVP), a Sinhalese nationalist group that opposes the presence in the country of Indian peacekeeping troops. Also contributing to the butchery was the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, which is fighting for a separate state for the Tamils, who make up 12.6% of the population and complain of discrimination by the majority Sinhalese. In the run-up to the balloting, Premadasa tried to placate the JVP by lifting the state of emergency imposed in 1983, releasing 1,400 JVP detainees and arranging the withdrawal of 5,000 of 70,000 Indian troops. As it has to other conciliatory gestures, the JVP responded with a killing spree. On election day, its fighters, who are strongest in the south, bombed and torched polling stations, planted land mines in roads, and ambushed convoys carrying ballot boxes. In the north, Tiger guerrillas attacked Indian soldiers and tried to cripple bus service by warning drivers not to report for work. As a result, only 64% of the 9.37 million electorate voted, compared with the 86.7% who turned out in the previous parliamentary election, in 1977. The unrest almost certainly worked to the UNP’s advantage, just as it had in last December’s presidential race, in which only 50% of the electorate went to the polls and barely gave Premadasa the edge over opposition leader Sirimavo Bandaranaike. As the ruling party, the UNP controls the police and military and was thus better able than the opposition to provide security at its rallies and to escort sympathizers to the polling booths. ‘In every country the ruling party enjoys an advantage. In this election we made full use of the advantage,’ acknowledged UNP chairman Mohamed Kaleel. Opposition parties, by contrast, were forced by the risk of violence to wage low-key campaigns. The Sri Lanka Freedom Party was especially demoralized by leader Bandaranaike’s narrow escape when several crude bombs were flung onstage and exploded during a rally in the northern city of Hinguragoda. In the south only Premadasa, heavily guarded, was able to address public meetings. Others had to canvass for votes at weekly fairs and street-corner ‘discussions’ that attracted at best a dozen people. JVP rebels even waylaid mailmen and burned their bags to destroy campaign literature that had been posted to voters. The opposition parties, however, benefited from the new proportional representation system, implemented in a general election for the first time last week. In 1977, for example, the SLFP won 29.7% of the vote but secured just eight seats. This time it did only marginally better, with 31.8% of the vote, but took 67 seats. Two Tamil groups allied with the moderate Tamil United Liberation Front won ten seats with just under 5%. Members of the Tiger-allied Eelam Revolutionary Organization who stood as independents took an additional 13 seats. With the UNP’s previous majority in Parliament considerable reduced, Premadasa considerably may have a tough time implementing his promised janasaviya (people’s strength) program. The plan would provide a monthly allowance of $75 to 1.4 million families, nearly half the nation’s population. Apart from easing rural poverty, the program, Premadasa calculates, would erode JVP support in the more backward areas of the south. The President has not specified where he would get the required funds. In the likely event that the plan fails, the UNP may have to take a more direct approach in dealing with the Sinhalese rebels. Premadasa was eager to befriend both the JVP and the Tigers and offered to ‘meet them for negotiations at any place and at any time’. But within the ruling party, says Land Minister Gamini Dissanayake, ‘there is a consensus that we must deal with them [the JVP] firmly.’ According to aids, Premadasa will probably continue a ‘two-tier’ policy of trying to coax the rebels into joining the political mainstream while quietly sanctioning a crackdown against them. Said the President after the election: ‘The agenda is clear. We must restore law and order.’ [reported by Anita Pratap/Colombo] ***** |

||

|

|||

The team members arrived in Point Pedro shortly after the city was bombarded by the Sri Lankan military in June 1987 in an attempt to flush out the guerrillas of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. ‘It was an emergency situation,’ says Dr. Jean-Louis Menciere, 38, an anesthesiologist from Paris who has completed two tours in Afghanistan for MSF and is on his second assignment in Sri Lanka. ‘The government asked MSF to send a surgical team because there were a lot of injured and no one to operate on them. The last surgeon had left Point Pedro in December 1985.’

The team members arrived in Point Pedro shortly after the city was bombarded by the Sri Lankan military in June 1987 in an attempt to flush out the guerrillas of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. ‘It was an emergency situation,’ says Dr. Jean-Louis Menciere, 38, an anesthesiologist from Paris who has completed two tours in Afghanistan for MSF and is on his second assignment in Sri Lanka. ‘The government asked MSF to send a surgical team because there were a lot of injured and no one to operate on them. The last surgeon had left Point Pedro in December 1985.’ The United National Party (UNP) emerged victorious, taking 125 seats in the expanded 225-member Parliament. But that was well short of the five-sixths majority President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s ruling party commanded before the election; it was not even the comfortable two-thirds majority mandate he sought. The twisted plait of balloting and bloodletting, now all but customary after 5½ years of civil strife, only testified to the magnitude of the winners’ task of restoring order.

The United National Party (UNP) emerged victorious, taking 125 seats in the expanded 225-member Parliament. But that was well short of the five-sixths majority President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s ruling party commanded before the election; it was not even the comfortable two-thirds majority mandate he sought. The twisted plait of balloting and bloodletting, now all but customary after 5½ years of civil strife, only testified to the magnitude of the winners’ task of restoring order.