The Mindset of the Sri Lanka Government

“Sri Lankan Identity” is a “Sinhala Identity”

Nagalingam Ethirveerasingam, Ph.D.

Identity

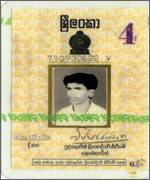

Those who design, approve, reproduce and issue Sri Lanka’s National Identity Card (NIC) and passports have a mindset that precludes them from accepting that the Tamils living in Sri Lanka have equal rights, and that they have an identity of their own.

The NIC has no inscription in Tamil. This assumes that the identity card is for perusal by those who can read the Sinhala language only - that is the police and the army. It also reminds the holders of the NIC, and who demand it to be shown that in the opinion of the government, the Sri Lankan identity is the Sinhala identity.

|

|

The

Sri Lanka’s Identity Card |

In Sri Lanka the NIC is used to determine the individual’s ethnicity (Tamil, Muslim or Sinhalese), and place of residence (NorthEast, Government controlled areas or Tamil rebel controlled areas). Tamils who live in Jaffna and Trincomalee have to register at the police station and are issued an additional identity card. Tamils in Jaffna have to post the householders’ list outside the door of the house for inspection by the security forces.

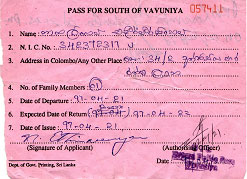

The NIC is used to identify, monitor and control the movement of Tamils within Sri Lanka. For example, if a Tamil travels from the rebel controlled areas to the government controlled area of Vavuniya, that Tamil is not allowed to stay in Vavuniya without a pass and also not allowed to go to the South without another pass. A Tamil cannot stay in the South for long unless he is registered as an occupant in a household in the South. The pass or “Visa” required to travel to the South is shown below. The form is in English but completed in Sinhala by the police.

|

|

The Pass |

Tamils to whom the pass is issued must sign it even though they cannot read the Sinhala language. The fact that the constitution and the law require the government officials to respond to Tamils in the Tamil language does not bother the police and the armed forces that are composed of 99% Sinhalese. The way I can get a ticket for a bus or train to travel South of Vavuniya is to sign the form and showing the pass issued by the police in Vavuniya to the ticket seller. Note that the pass is valid only for one day. I have to leave Vavuniya to the South or go back to the Tamil areas within 24 hours. Ironically, the Sinhala government is recognising that Tamils have a homeland and if they wish to travel outside it they get a “Visa.”

National Passports and Sri Lankan identity

The evolution of the Sinhala Sri Lankan identity and the second-class status delegated to the Tamils is illustrated by the changes by the inside cover of the Ceylon and later the Sri Lankan passports shown below. Tamils were in fact challenged to assimilate or face discrimination. Tamils response was not to be assimilated and establish a separate state in their traditional homeland. Sinhala leaders never expected the Tamils to take up arms to defend themselves and protect their rights. After each pogrom the Tamils demonstrated the classic “battered wife syndrome” by going back to the Sinhala leaders for more beatings in 1958, 1961, 1977, and 1983. They hoped each time they went back that their rights would be recognised, and hoped that peace will be theirs. They did not realise that the idea of second-class status of the Tamils is deeply imprinted in the psyche of the Sinhala Buddhist leaders. The National flag, the NIC and the Sri Lankan passports reflect an aspect of the deeply ingrained racism.

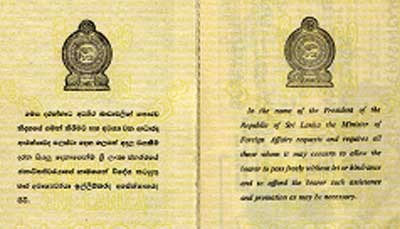

In the 1952 and 1962 passports, the inside cover showed the request of the government to those who would examine the passport. It was printed in English only. There was no Sinhala or Tamil translation of it (See below). On the face of the cover was printed CEYLON, and PASSPORT only in English.

|

|

|

| 1962 Passport | 1971 Passport |

The 1971 passport showed the same cover titles in Sinhala and a translation of it in English. The inside cover had the request printed in Sinhala only. A translation of the request in English appeared on the opposite page. There was no Tamil version.

|

|

|

1976 Passport Facing Pages |

The front cover of the 1976 passport was also in Sinhala and English but had the new name of the country - Republic of Sri Lanka printed on the cover (See above). The symbol on the front cover and the inside cover had changed from the lion-crest to the throne. There was a translation of the Sinhala text in English on the inside cover on the opposite page, but there was no translation of it in Tamil.

|

|

|

1986 Passport |

The design of the 1986 passport took a different turn. The face cover now had the titles in all three languages. But on the inside cover a rectangular Sinhala motif border enclosed the Sinhala text and the Sinhala symbol of Sri Lanka - the throne with a lion. The Tamil and English translation of the inside cover appear outside the borders on the opposite page. The intention of the government administration is to maintain an ethnically pure Sinhala identity for Sri Lanka and recognise the other ethnic groups as minorities with second-class citizenship outside the border. The inclusion of the Tamil translation is to please the Tamils who support the Sinhala party in power and to show to the international community the so-called concessions the government had made to the Tamils.

|

|

|

1996 Passport Facing Pages |

In the 1996 passport, even after the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord of 1987, there were no changes to give the Tamil language equal status within the borders. It is similar to the 1986 passport except for the smaller size and addition of lotus flowers at the bottom borders of the inside cover. Considering how easy it is to reduce the size of the symbol, and insert the Tamil translation, the design is a deliberate message to indicate the place of minorities in Sri Lanka and to remind them that they play only second fiddle to express the Sinhala theme. The Pacts, Accords, All-Party conferences, Select Committees, Commissions and public statement of peace talks and promise of equal rights are empty promises to keep foreign aid and investment flowing into the country. Until there is a change of mind and heart to accept Tamils as equals, there will be no genuine move towards negotiations and peace.

The evolution of the design of the passport is cleverly crafted to depict the identity of Sri Lanka and to put on a false face that Sri Lanka honours the language of a minority group, which also occupies the island. Thereby denying that the island was also the home of the Tamils who lived and ruled their own kingdom in specific parts of the island for more than 2000 years.

Without a mindset that would accept that the Tamil community is equal to the Sinhala community, and accepting that both communities, with the Muslim community, share the island as their home, no negotiation will bring a peaceful resolution to the violent conflict.

The arrests, torture, rape and murder of Tamils by the Sri Lanka armed forces continue to this day with impunity. The Sinhala Sri Lanka press does not report all the human rights abuses. The Sri Lanka government continues the war destroying the infrastructure in the Tamil areas, laying siege of the Tamil community and delaying peace talks to give expression to the Sinhala leaders’ idea of racial superiority over the Tamils that is deep seated in their psyche.

The international community, to ensure peace, should act as mediators to achieve a solution and put an end to human rights abuses. If such assistance is not forthcoming, the United Nations should assist the Tamils to give expression to their right to self-determination.

30 June 2001