Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||||||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Sri Lankan Tamil StruggleChapter 8: Growth of Nationalismsby T. Sabaratnam, September 16, 2010

The Background The British arrived in Sri Lanka when the people were returning to their original faiths. The Sinhala people in the Low Country were returning to Buddhism and the Tamil people of the north and east were getting back to Hinduism. The process that started in the second half of the Eighteenth Century when the Dutch reduced their pressure of religious conversion gathered momentum after the advent of the British. Most of the famous Buddhist and Hindu temples were rebuilt in the second half of the 18th Century. Nallur Kanthaswamy Kovil, the first of them, was rebuilt in 1750 and the Vannarponnai Sivan Kovil a few years later. Kelaniya Vihara which was destroyed in 1557 was rebuilt in 1767. When the British East India Company took over the Dutch possessions in Sri Lanka, Protestantism (Calvinism) was the state religion and two types of schools, Parish schools of the Dutch Reformed Church and the traditional Sinhala and Tamil village schools existed. The Company ordered the closure of the parish churches and schools run by the Dutch Reformed Church and arrested the priests. They also stopped the payment of the teachers of Parish schools. The ban did not affect the Sinhala and Tamil schools. The ban on the Parish schools and the arrest of the priests created a vacuum in Christian religious and educational fields. The religious network run by the Dutch Reformed Church and the European system of elementary education collapsed. The Lieutenant Governor who was responsible for the administration of the territories disclaimed any responsibility for religion and education saying that they were not his concerns. Sri Lanka was made a crown colony in 1802 and Fredrick North was appointed governor. He ordered the release of the Dutch priests and tried to revive the Parish schools. His attempt failed. North’s administration announced in 1805 that in matters of religion its policy was one of neutrality. All laws against the Roman Catholics were rescinded the next year. The announcement of neutral religious policy and the removal of all restrictions on Roman Catholics completed the collapse of the Dutch Reformed Church in the entire island. With compulsion and economic benefits removed the people went back to their original religions. Statistics that reflect the state of affairs during that period tell the real story. In 1801 the estimated population of Sri Lanka was about 1.5 million people. Of them the number of Protestants was estimated at 342,000, while the Roman Catholics were considered to be still more. In 1804, the Protestant Christians were estimated at 240,000, in 1810 they had dropped to 150,000, in 1814 to 130,000 and fifty years after in 1864, there were said to be 40,000 Protestants and 100,000 Roman Catholics.

In the Tamil-dominated north and east the situation was worse. Rev. Samuel Newell, the first American missionary to arrive in Sri Lanka captured the situation that prevailed in Jaffna in 1813 thus:

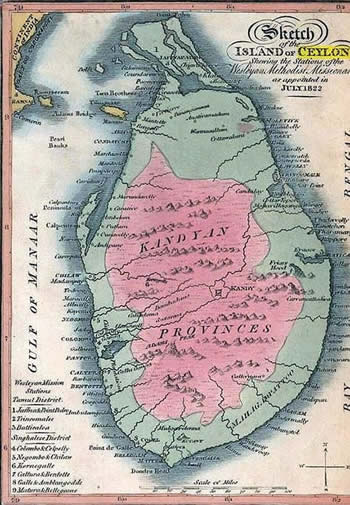

By idolaters Newell meant idol worshiping Hindus. Three years later Rev. Daniel Poor whom we quoted at the end of the last chapter confirmed Newell’s statement. According to Newell, in the single Protestant congregation in the Jaffna there were only two persons capable of instructing the people on the Bible. One of them was Rev. Christian David, a native of Thanjavur. The other was the Dutch Mrs. Schrawder who held regular meetings in which she read the Scriptures and explained them in Tamil. The Buddhists and the Hindus who returned to their old faiths rebuilt the temples in their areas. In the Sinhala areas only about 200 Buddhists survived the Portuguese and Dutch periods. By the end of the second decade of the 19th Century the number of Buddhist vihares and monasteries had exceeded 2,000. The situation in the Tamil territory was similar. Murugar Gunasingam says in his book, Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: A Study of its Origins (MV Publications, Sydney 1999), that there were 329 Hindu temples in Jaffna in 1814. He says that many of them had come up in the first two decades of British rule. The British Colonial Office was perturbed by this situation. It instructed Governor Brownrigg, who succeed North, to help the promotion of the Protestant religion. The British Colonial Office gave that order because it was influenced by the First Great Religious Awakening that swept Great Britain and the North American colonies. The Methodist campaign which caught the imagination of the British people stressed the need to spread Christ’s teachings to the people in the British colonies. John Wesley’s slogan, "Bible, cross, conversion, and activism," attracted the British people. Protestant missionaries from England and America came to Sri Lanka with the intention of filling the void. The missionaries reached Colombo and Jaffna during the second decade of the 19th Century. Arrival of Missionaries The first Protestant Mission to arrive Sri Lanka was from the London Missionary Society. Its mission which comprised four Germans arrived in Sri Lanka in 1805. Three of them left for India and Rev. J.D. Palm served as a pastor at the Dutch Church at Wolfendahl in Colombo. The pioneer of modern missions in Sri Lanka was the Rev. James Chater who landed in Colombo on April 16, 1812. He was sent out by the Baptist Missionary Society in 1806 to join the Serampore Mission in North India, but his landing was opposed by the Indian Government, so he went on to Burma and commenced work there. Civil war in the Burmese dominions and the ill-health of his wife forced him to come to Sri Lanka. Governor Brownrigg welcomed him and helped him in his missionary work. The Baptist Church was never strong in Sri Lanka. Its principal stations were at Colombo, Kandy, Matale and Ratnapura. The Ceylon Auxiliary of the British and Foreign Bible Society was the next mission to come to Sri Lanka. It reached Colombo on August 1, 1812. The Wesleyan Methodists were the next. New interest in spreading the Christian faith in the new British colonies emerged during the latter part of the first decade of the Nineteenth Century. In 1813, the British Conference of the Methodist Mission decided, after lengthy debates, to send missions to Ceylon, Java and the Cape of Good Hope.The 7-member mission headed by Dr. Thomas Coke was sent to Ceylon. The mission left on December 30, 1813. Two of them, the mission leader Dr. Coke and Mrs. Ault died on the way. The remaining five - Brothers Lynch, Squance, Ault, Erskine and Clough - reached Galle on June 29, 1814. The Methodist Church observes that date as Methodist Day. The mission was active in religious and educational work in all parts of Sri Lanka. Two of them, Brothers Lynch and Squance went to Jaffna, Brother Ault to Batticaloa, Brother Erskine to Matara and Clough remained in Galle. The 2-member Jaffna group - Lynch and Squance - which reached Jaffna on August 1814 was joined by Rev. Christian David, a South Indian Tamil pastor who was serving in Jaffna during the Dutch period. The missionaries studied Tamil and held services in the Jaffna Fort Church. The Wesleyan Methodist Mission bought on August 1, 1816 an old orphanage and Lutheran Church opposite the Jaffna esplanade. The building was converted into an English school the next year and named Wesleyan English School with Rev. Lynch as principal. The preachers met annually in Galle and in the third conference held in January 1819 they divided Sri Lanka into two districts and designated them as Sinhalese and Tamil districts. Three young missionaries including Rev. Joseph Roberts joined the Jaffna group in 1820; Roberts became famous for his work Oriental Illustrations. Roberts pioneered the building of a new chapel on the other side of the road which was completed in 1823.

The five- member Jaffna group was very active from the beginning and the mission’s report for 1825 said that its work on education was phenomenal. In just ten years it had established 26 schools which had 795 students. One of the schools in Jaffna town was for girls and it had 40 students. The principal of the school was the respected Dutch lady Mrs. Schrader. Rev. Peter Percival replaced Roberts who returned to England. Percival who was involved in educational activities in Calcutta paid greater attention to the development of schools. He reorganized the Wesleyan English School and named it Jaffna Central School. He also opened English schools in all the principal cities where Wesleyan missionary stations had been established. In 1837 a girl’s boarding school was started with six girls which grew into Vembadi Girls High School. Percival retired at the end of 1852 after serving in Jaffna for 26 years. His period transformed the religious, educational and social environment of Jaffna. His major achievement was the translation of the Bible into Tamil. Arumuga Pillai (later Arumuga Navalar) assisted him in this historic endeavour. The principal educational institutions established by the Wesleyan Mission were: Wesley College in Colombo opened in 1874, Richmond College, Galle, 1876, and Kingswood College, Kandy, 1891.The next Christian mission that arrived in Sri Lanka was The American Ceylon Mission (ACM). Rev. Samuel Newell was the first American missionary to arrive in Sri Lanka. He and his wife Harriet were sent to India in 1813 by the Prudential Committee of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Mission which was founded in Boston in 1810 by six Theology students who consecrated themselves in the service of God, in preaching the Gospel of Christ in heathen lands. Newell decided to go to Calcutta because a Christian mission was already there. William Carey, the Father of the Modern Christian Missions (Baptist Missionary Society, 1792), had founded the Serampore University in Bengal and had established a printing press. He published extensively in many Indian languages and built up one of the best multilingual libraries in the East. Carey was a great encouragement to the American Ceylon Mission which followed his example in education, translations, printing and publishing.

The British asked Newell to leave India when he entered Calcutta as it was just after the War of 1812 between the British and the Americans. The British suspected him because he was an American. The Newells went to Mauritius where he lost his wife and only child. He then left for Bombay but the ship touched Galle in Sri Lanka. He landed in Galle in February 1813 and proceeded to Colombo. He called on Governor Sir Robert Brownrigg, a supporter of missionary enterprise. The governor advised Newell to select Jaffna, as the British administration was suspicious of Americans. He wanted Newell to be away from Colombo. Newell spent one and a half months of his 10-month stay in Sri Lanka in Jaffna. Newell was impressed by the peaceful atmosphere that prevailed in Jaffna and by the eagerness its inhabitants showed for learning. In his letter to the American Board of Commissioners Newell recommended Jaffna as the most suitable location for American missionary work. The Board which accepted Newell’s recommendation sent a 4-member team consisting Revs. Warren, Richards, Meigs and Poor which reached Colombo in early 1816. Warren who travelled overland reached Jaffna on July 11, 1816 while the others joined him later. Right from the start the American Ceylon Mission (ACM) focused its attention on religion, education, medical care and printing. They were trailblazers in these fields. The Mission opened its first chapel in Tellipalai. Within the next decade it had eight stations under its supervision. They were at Tellipalai, Vaddukoddai, Uduvil, Manipay, Pandatharripu Chavakachcheri. Varani and Udupiddy. It also had six outstation prayer halls at Atchuveli. Moolai, Karaitivu, Velanai, Kayts and Pungudutivu. The mission received a reinforcement of ordained American missionaries during 1833-34 and thereafter the strength of the American missionaries in Jaffna was raised from seven to nine, which included a physician and a printer. Religious service was held regularly in those stations and frequently in some of the neighbouring villages. Religious meetings were held in the evenings and the priests visited the homes of the church members and held special services. They preached at market places and street corners to spread the message of the Gospel. Rev. Edward Warren who took special interest in education found the environment in Jaffna suitable for intense educational work. He started the first American missionary school in Tellipalai in 1816. The American Mission founded the Uduvil Girls School in 1824, the first girls’ boarding school in Asia. The ACM kept up its interest in opening Tamil and English schools and by 1848 it had under its control 105 Tamil schools and 16 English schools spread across the Jaffna peninsula. Boarding schools were opened at Tellipalai, Pandatharippu, Manipay, Uduvil and Vaddukoddai. The Church Missionary Society (CMS) was the next Christian missionary group to come to Sri Lanka. It came into being on April 12, 1799 at a public meeting at the Castle and Falcon Inn, Aldersgate, London. Its roots go back to the middle of the Eighteenth Century when there was a revival in the Church of England inspired by the preaching of John Wesley and others. Although Wesley's followers left the Church (and founded Methodism), other Anglican clergy revived and reformed Anglicanism by bringing personal conviction into religion. Their emphasis on individual conversion and justification by faith led them to be called Evangelicals. By 1780s two groups in London were particularly concerned with spreading the Gospel to the countries where its message was not heard. They were: the Eclectic Society, and the Clapham Sect. The discussions in the Eclectic Society about the needs and methods of missionary work led to the formation of the Baptist Missionary Society in 1792 and the London Missionary Society in 1795. At a meeting in March 1799 John Venn raised the specific question of how they should spread the Gospel overseas and his call for action led to the April meeting at the Castle and Falcon. There a resolution was passed, "It is the duty highly incumbent upon every Christian to endeavour to propagate the knowledge of the Gospel among the Heathen;" and the Society for Missions to Africa and the East was formed (in 1812 renamed The Church Missionary Society for Africa and the East). The first CMS mission went out in 1804, and the first English clergy to work as the Society's missionaries went out in 1815. The CMS appointed four English clergymen - Revs. Samuel Lambrick, Benjamin Ward, Robert Major and Joseph Knight - to commence operations in Sri Lanka. They left England on December 26, 1817 and reached Galle in June 1818. They decided to begin their work in four different stations. Rev. Lambrick went to Colombo, Rev. Ward proceeded to Trincomalee, Rev. Knight travelled to Jaffna and Rev. Major stayed in Galle. Rev. Knight commenced work at Nallur in 1818. Nallur being the capital of the Jaffna Kingdom and the citadel of Saivaism Knight had to face stiff resistance. People there treated him as an outcaste and refused to associate with him. They believed that admitting him into their houses would pollute them. The Tamil Pandit who taught him Tamil grammar and language bathed on his way home to purify himself after every lesson. Rev. Knight was not deterred. He succeeded in opening a church and a school named Boy’s English School in Nallur in 1823. It was run by Rev. William Adley. In 1841 it was transferred to Chundikuli to make room for the Girl’s Boarding School. In 1846 the school was removed to its present site adjoining St. John’s Church, The school was renamed St. John’s College. He opened a church and a school in Kopay in 1849. In Nallur he started a Girls’ Boarding School. The CMS like the Wesleyan and American missions recognized the need to interact with the indigenous people and the value education played in religious conversion. They conducted the services in English and Tamil. The English service was conducted every Sunday and the Tamil service once a fortnight. The annual reports of the mission indicate that indigenous people showed greater interest in the English service because the British who lived in Jaffna attended them. They made use of the Church to befriend the British. The locals also gradually adopted the English way of life and culture. Differing levels of Resistance As noted earlier, when the missionaries came to Sri Lanka the people were getting back to their old faiths which they had been practicing in their private life during the Portuguese and Dutch periods. There was an atmosphere of enthusiasm about religious revival in the low country and in Jaffna. Thus they looked at the entry of the missionaries with suspicion. They feared a possible reintroduction of Christianity, The level of suspicion and resistance differed significantly among the Buddhists and the Hindus. Their respective experience and outlook were the cause. Religious conversion was severe in the Tamil areas during the Portuguese and Dutch periods. Both worked with the objective of turning the Tamil territory into a bastion of Christianity. Portuguese claimed Jaffna was totally Roman Catholic. The Dutch boasted that they had turned Jaffna into the citadel of Protestantism. Both the Portuguese and the Dutch were more tolerant in the Low Country Sinhala area. The existence of the Kandyan Kingdom and the attitude of tolerance Buddhist monks showed to Christianity in the early years of the British period made the Buddhists to adopt an accommodative approach to Christian missionaries. Prof. Gananath Obeyesekere in his Colonel Olcott lecture in 1992 quotes Buddhist scholar Kitsiri Malalgoda to say that the initial response of the Buddhist monks to Christian missionaries was “not unfriendly”. He says Buddhist monks even gave Christian missionaries permission to preach in their temples. Such cordiality never existed among the Hindus. They regarded the missionaries as outcasts and the action of the Pandit who bathed when he returned home after teaching Knight provides an example. The rigid caste system of the Tamils was another factor for their unfriendly attitude to the missionaries. The Protestant pastors, from the outset, campaigned against the caste system. They preached that before Christ all men were equal. High caste Hindus considered that an unwarranted assault on their social system. The mode of preaching adopted by the Christian preaches also created unease among the Hindus. Protestant pastors preached the Gospel in the market squares and street corners. Hindus looked at that with suspicion and dislike. Education as a Tool Brother James Lynch, one of the founders of the Wesleyan Mission in Jaffna gave the reasoning behind the opening of schools by Christian missions. He said, “Schools would help to establish congregations.” The missionaries considered education an indispensable tool to spread the Gospel. All the missions established schools near the churches they built. As pointed out earlier the first act of Rev. Lynch of the Wesleyan Methodist Mission was to establish the Wesleyan English School. He became its principal. In the first ten years of its existence the Wesleyan Mission established 26 schools in the Jaffna peninsula which included the Vembady Girl’s School. The CMS also followed the policy of opening schools. It opened its first school, Boy’s English School at Nallur in 1823 which was shifted to Chundikuli and named St. John’s College. It built several boys' and girls' schools. American Ceylon Mission which was allowed go work only in the Jaffna peninsula outdid the Wesleyan Mission and the CMS. It showed special interest in education and started the first American missionary school in Tellipalai in 1816. It founded the Uduvil Girls School in 1924. It opened Tamil and English schools across the Jaffna peninsula and by 1848 it had under its control 105 Tamil schools and 16 English schools. Batticota Seminary The American Ceylon Mission’s special contribution to Jaffna was the establishment of the Batticota seminary. It played a large part in propelling the Tamils from medievalism to modernity by introducing rationalist and scientific modes of thinking. It helped transform Jaffna’s education from the traditional guru kula system to classroom teaching. It also widened the scope of education to include geography, history, mathematics, algebra, astronomy, science and medicine. The American Ceylon Mission was the first mission to provide collegiate level education. It founded the Batticota Seminary at Vaddukoddai on July 22, 1823 with Rev. Dr. Daniel Poor as its first principal. It provided tertiary level education equivalent to the College education imparted in the New England region of America. The founders of the Batticota Seminary wanted to establish a degree certificate awarding college like those in America but political conditions in Sri Lanka in 1823 was hostile to them. Edward Barnes who became governor in 1821 was suspicious of the Americans. He had fought under Wellington at Waterloo and thus had a sentimental hatred against Americans as America had fought with Britain during the Napoleonic wars. He refused to issue a charter to establish a college. The American Ceylon Mission overcame Barnes’s resistance by opening a seminary but he continued to impose hurdles on it. He banned the arrival of American missionaries during his term of office, 1821-1832. When James Garrett, an American missionary, arrived with the printing press he was ordered to leave the country. Thus six of the nine American missionaries who were in Jaffna in 1823 – Daniel Poor, B.C. Meigs, Miron Winslow, Levi Spaulding, Henry Woodward and John Scudder – were made trustees of the seminary. All the American missionaries who served in the early Nineteenth Century left their imprint on Jaffna society. They were all pioneers in the fields they elected to serve. Poor was principal of the Batticota Seminary till 1836. He held the wider view that education should have as its objective not merely the training of a band of evangelists but the creation of a wide impact on society. Batticota was able to get down new American professors only after Barnes retired in 1831. Nathan Ward who arrived in 1833 was professor of mathematics. James Eckard who arrived in 1834 handled all subjects. Henry R. Hoisington who arrived in 1836 taught Hindu Astronomy. He succeeded Poor as principal in 1845. Edward Cope joined Batticota in 1840 as Professor of English Language and Literature, Robert Wyman in 1843 as Professor of Social Literature and Evidences of Christianity, E.P. Hastings in 1847 as professor and was principal in 1850 and later in 1854 to 1855 when the institution was closed. Professor C.T. Mills was principal during 1851 – 1853 and M.D. Sanders principal during 1853- 1854. Two others J.C. Smith and W. Howland served as professors during the last years of the institution. Only 12 American missionaries worked with Batticota in the 31 years of its existence and teaching was done with the assistance of native teachers, who at any given time did not exceed five. Only 27 natives taught during the entire period of its existence. Those who taught during the later years were the institution’s old pupils. Some of them like Carol Vishvanathapillai, Evans Kanagasabaipillai, Nevins Sithamparapillai and Henry Martyn left indelible marks on the social history of Jaffna. English was the medium of instruction in the Batticota seminary and the missionaries who started it firmly believed that an English education would enhance the opportunities of the Tamil people. They, especially Poor, soon recognized the antiquity and richness of the Tamil language and decided to respect and foster it and its culture. They also realized the strong hold Saiva Siddhantha philosophy had on the people and that to make Christianity reach the people they should use the Tamil language as a vehicle. So, instilling a through knowledge of the Tamil language became the basis of a Batticota education. A study of the courses of study developed by the Batticota Seminary show that Tamil was first used to explain the new concepts. Then the ability to translate the course material into Tamil was cultivated. By about 1830 the need to teach basic Tamil grammar and literature was realized. According to the Annual Report for 1830 the seminary had begun to teach Nanool and Auveiyar Muthu Moli and Moothurai. They had also begun to teach Thirukural and Skanda Puranam. Finding it difficult to get students with adequate knowledge of the English language, the Seminary, in the process of developing the course content, lowered the admission requirement of English language and raised that of Tamil. Medicine in Tamil The American Ceylon Mission, from the outset, concentrated its attention on medical care. Dr. John Scudder, the first medical missionary to the East, opened a medical center in Pandaitharippu in 1820. It was the first Western Medical Mission in Asia. Dr, Scudder served for 19 years in the dual capacity of clergyman and physician. He was especially successful in the treatment of cholera and yellow fever. Dr. Nathan Ward succeeded him in 1836. He opened a medical ward at Vaddukoddai. He was replaced by Dr. Samuel Fisk Green in 1846. Dr. Green’s 30-year medical practice and training program had a great impact on the Jaffna peninsula. Dr. Green arrived in Jaffna in 1847 and was posted to Vaddukoddai. He was moved to Manipay the next year. At Manipay, he established a hospital and a

medical school to teach Western medicine. His 25- year service as a medical missionary transformed the health care scene of Jaffna. Dr. Green’s vision when he started the medical school was to build a network of western medical doctors in the villages of the Jaffna peninsula. He soon found that the doctors he trained found employment in the government medical department and migrated to the cities. Then he realized that to make his vision realizable the training should be imparted in Tamil. He started the switchover to Tamil in 1855 and completed the process in 1864. In the 20 years of service at Manipay he trained 62 doctors of whom 29 were in the English medium and 33 in Tamil. Dr. Green found that the switchover to Tamil was no easy task. Standard and precise medical terms had to be discovered or coined. Medical literature had to be translated or written, Above all, scientific language had to be developed as distinct from the prevailing literary language. Dr. Green undertook the translation of medical textbooks into Tamil with the assistance of Dr. Evarts. The work was completed the next year. By the 1850s, he had translated more than 4,000 pages of medical texts into Tamil. The first textbook Green selected for translation was Dr. Calvin Cutter’s Anatamy, Physiology and Hygine. He read the proof and supervised its printing. In the next 27 years the Medical School translated eight other standard medical textbooks. He also compiled three glossaries of Tamil words for medicine and science terms. One of them was Diseases of women and children and Medical Jurisprudence. By the end of 1854 a cholera epidemic struck Jaffna. Green wrote a booklet explaining how to handle that disease. Poor had an attack of cholera and died. Green himself had an attack but survived. He wrote three books on popular subjects like The Mother and Child. He wrote 12 pamphlets like Be Clean, The Way of Health to educate the public. Translation of medical textbooks into Tamil requires tremendous effort. Finding appropriate technical terms was a major task. Dr. Green can be regarded a pioneer in that field. The rules he adopted in coining the technical words were: Brevity, Appropriateness and Explanatory. In the process of coinage he followed the norm:

American Ceylon Mission’s textbook writers and Dr. Green should be credited with developing science writing in Tamil. They developed a style where care was taken in the choice of simple, unambiguous words, conveying the ideas in clear language, making the sentences simple and clear. They wrote short paragraphs. After Dr. Green’s departure medical classes were conducted with local instructors, Medical work was done by local physicians. Dr. T,B. Scott and his wife Mary came in 1889 and reopened the medical ward in Manipay. Under them Manipay Hospital recorded significant growth between 1893 and 1898 Women’s Medical Mission started its work and McLeod Hospital at Inuvil was opened. Dr. I.H. Curr took charge of the Inuvil Hospital. A new Maternity Ward was opened at Inuvil in 1911. During the next 20 years Inuvil Hospital was developed. Printing and Publication The American Mission established the first printing press in Jaffna in 1820 and, in 1841, the island's fifth newspaper – Morning Star – and the first Tamil-language newspaper, Utayatarakai were printed on it. In 1862, Rev. Moron Winslow’s Comprehensive Tamil-English Dictionary was printed on that press. The seminary undertook to research and publish pioneering books in the Tamil language in subjects like literature, logic, algebra, astronomy and general science. After the late 1840s, the seminary underwent serious financial crisis. It started collecting entrance fees thus enabling only wealthy families to send their children for education. They were reluctant to adopt Christianity thus defeating the primary purpose of Christian education. The Rufus Anderson Commission sent to assess the spiritual achievements of the educational institutions considered non-Christians receiving the benefits of Christian education without adopting Christianity an abuse. The Commission recommended the closure of the seminary. It was closed in 1855. During the 31 years of its existence 670 students completed their education in the seminary, Most of them were from Valigamam where a majority of the boarding schools were located. After the commencement of the seminary all boarding schools except the one at Tellipalai were closed. The Boarding School at Tellipalai was converted into a preparatory school for the seminary. Jaffna’s Christian community was frustrated by the decision to close the seminary. It launched an agitation calling for the reopening of the seminary. Jaffna College was opened after 17 years of agitation in 1872. The College provided primary, secondary, and post-secondary education. From the very inception Jaffna College played a distinct role in the pursuit of higher learning. It had a residential community of missionaries, principals, teachers, students and helpers. Its hostel became the motivator of social and political changes in the Jaffna peninsula. By the middle of the Nineteenth Century Christian missionary activity was fairly widespread in the Jaffna peninsula. Of the 32 parishes in Jaffna the American Mission worked in 17 with a population of 126,631 persons, CMS served in 10 with 44,458 persons and the Methodists in 3 with 35,251 persons. But the missionaries were not happy with the result. Their hope that Protestant Christianity would take root in the Jaffna peninsula had failed. Rev. Lambrick of the CMS who went to Colombo established churches and schools there and expanded his work to Kandy where a church and a school were built in 1857. The school was named Trinity College in 1872. The church too developed and the first two Singhalese clergy were ordained in 1839. The Sri Lankan mission which had functioned all those years as part of the Madras diocese was granted its own Bishop in 1845. From the 1850s CMS commenced work among the plantation Tamils. The American Mission which the East India Company did not permit into India until 1832 used Jaffna as the stepping stone to enter Tamil Nadu from that year. Thus Jaffna lost a stream of outstanding American scholars and doctors to India starting in 1832. Dr. Daniel Poor and his colleagues founded the American Madurai Mission and the well known American College in 1834. This great educator and evangelist of Jaffna and Madurai returned to Jaffna as an evangelist and died in the cholera epidemic in 1855. His wife and children had died of cholera a few years earlier. They all lie buried in the Missionary Cemetery adjacent to the Tellipalai Church. Protestant Christianity failed to take root in the Jaffna peninsula due to the Hindu revival that surfaced during the mid-19th Century. It was the reaction against the preaching and activities of the Christian missionaries that kindled the dormant religious nationalism among the Hindus and Buddhists of Sri Lanka. (Next week: Religious Revival) --------------------------------------------------------------------- Index Emergence of Racial Consciousness Growth of Nationalisms

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||