Ilankai Tamil Sangam29th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Who Killed Rajani Thiranagama?How convincing is the grapevine news?by Sachi Sri Kantha, September 18, 2010

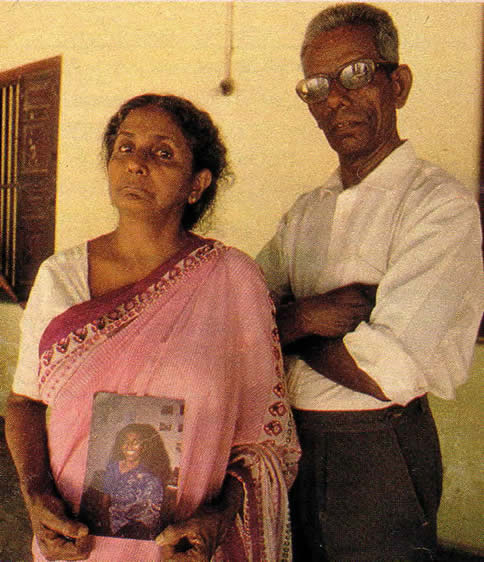

As I have stated previously, Dr. Rajani Thiranagama (1954-1989) was a junior acquaintance of mine, during my university days. I provide below, one item from my files to mark her 21st death anniversary that falls on September 21st. This is a feature with somewhat of a derisive caption “The Battle for No Man’s Land” by John Merritt that appeared in the Observer magazine (London) of April 29, 1990. A more appropriate title would have been the first question in the title of this commentary, which appears in the second and penultimate paragraphs of John Merritt’s feature. It includes the thoughts of Dr. Thiranagama’s parents on the death of their daughter. Their photograph, taken by Roger Hutchings, which accompanied this feature is reproduced here.

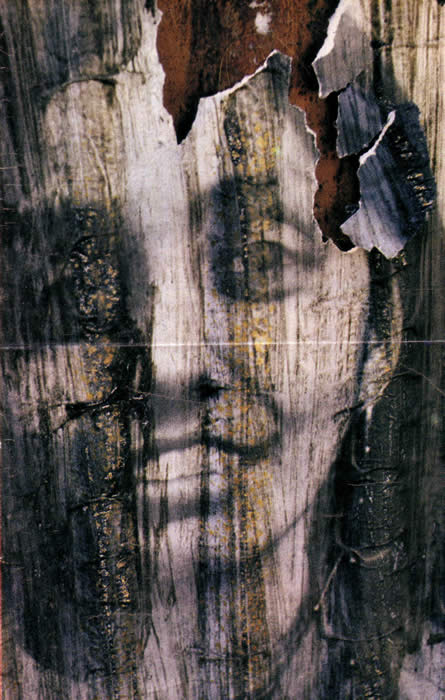

I provide this item for the record, as I couldn’t find the complete text on the internet posted by anyone (including Dr. Thiranagama’s circle of friends!), other than some excerpts of the article that I quoted in my Pirabhakaran Phenomenon series (part 24). [www.sangam.org/PIRABAKARAN/Part24.htm] I provide the text here, (1) especially for the testimonial emanating from Rajani’s father Mr. Rajasingham, which faulted the IPKF and GOSL military (2) descriptions that accuse the IPKF of massacres and atrocities against Jaffna Tamils. I vaguely suspect that it is for these reasons that the complete text of Merritt’s article has been conveniently ‘forgotten’ by Rajani Thiranagama’s immediate circle of friends (who had to later collude with India’s gumshoes and the Sri Lankan authorities, for their sustenance). This feature provides evidence, via Mr. Rajasingham’s testimony, that Dr. Thiranagama was harassed by the IPKF and Sri Lankan military, while she was alive! It does not mention anywhere that she was harassed by the LTTE, while she was alive! Of course, as one would expect, it provides blanket criticism of the LTTE’s policies, probably fed by Merritt’s Tamil hosts while he was in the island. The Battle for No Man’s Land by John Merritt [Observer magazine, London, April 20, 1990, pp. 46-52.] [Note: the dots, wherever they appear, are as in the original.] On bullet-blasted walls in the city of Jaffna, northern Sri Lanka, anonymous hands have pasted pictures of a young woman. Crow-black hair frames her face; her eyes have the sad but vivid gaze of an icon. She is just one of an estimated 30,000 people killed last year alone in a country where murder comes second only to massacres. And, when the precise nature of every successive brutality seems to compete with the last to defy imagination, her death was relatively clean. Yet beside one of her pictures someone has posed the sort of question it is no longer usual to ask: ‘Who Killed Rajani?’ Rajani Thiranagama was a 35- year old doctor, teacher and mother of two young girls, 11- year-old Narmadha and nine year-old Sharika. But it was a different vocation that led to her death. A friend puts it simply: ‘She wanted the voices and opinions of ordinary people to be heard, their lives and their struggles and their brutal deaths not to be forgotten and buried in the debris of a ravaged society.’

Like most of the killings in a country where government regulations conveniently permit the disposal of bodies without any inquiry, her murder has never been investigated. Rajani’s mother, Mahilaruppiam, says: ‘People say my Rajani was foolish. They say she should have stuck to her work and stayed quiet about the killings. But she couldn’t see anyone suffer and she couldn’t accept the young people carrying guns. She said all killing was wrong – whoever did it, for whatever reason. And now we have lost our child and her children have lost their mother.’ Rajani, a Christian Tamil, had lived through the Sri Lankan government’s slow ruin of the island’s Tamil minority, with its weapons of stark deprivation and the suppression of the Tamil language in favour of the Sinhalese spoken by two thirds of the country’s 16 million population. When the pace speeded up it was natural that she should identify with the aspirations for survival and self-determination embodied by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, the LTTE – popularly known as ‘The Boys’. But then she saw, and began to speak against, the Tigers’ degeneration into what she believed was ‘a purely militaristic organization, exploiting the youth, with a callous disregard for the people.’ Her mother still talks of Rajani in the present. ‘You see, my Rajani wants to see the killings stop and she has to side with those who don’t carry guns.’ After church on Sunday Mahilaruppiam sits with her husband Rajasingham, a former college and hospital administrator, on the long veranda now overlooked by an LTTE camp in a house commandeered from relatives who have fled abroad. She says: ‘We are frightened, so it is better not to be so sure about who killed her. We are too old to leave. Perhaps there is no point in blame, we won’t get our child back.’ Rajasingham points to the LTTE camp: ‘For more than a year, before the Tigers were there, the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) occupied that property. They took away Rajani’s writings and the reports she had compiled on the killings. Before that, the Sri Lankan army, came here and destroyed many of our possessions and took away our family photographs.’ Government forces were hunting Rajani’s older sister, a former English tutor at Jaffna University and now a refugee in Britain, who was arrested with two doctors and a priest and accused of harbouring members of the LTTE. She was one of the few survivors of a subsequent prison massacre of hundreds of ‘suspects’. ‘So you see, what does it mean to ask who killed out Rajani, when everyone is killing everyone?’ Rajasingham asks. ‘Rajani was perhaps too honest. She once left a university senate meeting in tears because the university authorities wouldn’t agree to an inquiry into the murders of students by government and Indian forces. She had worked as a doctor among the Sinhalese people as well as the Tamils. There were people who said she shouldn’t do that. When she worked at Jaffna Hospital she was there day and night. I was on the board of a private hospital here and she would come and tell the poorest people, ‘Don’t come here, go to the public hospital and I will treat you for nothing.’ She was impossible, she stayed with the poor and the sick up until the moment she gave birth to her second daughter.’ Cutting short three months of research in Britain, Rajani came home to Jaffna just two weeks before her murder, to guide her students through their exams. She had written: ‘Every ‘sane’ person is fleeing this burning country – its hospitals have no doctors, its universities no teachers; its crumbled, war-torn buildings cannot be rebuilt because there are no engineers or masons or even a labour force; its families are headed by women; the old, the sick and the weary die without even the family to mourn or sons to bury the dead.’ Single handed she reopened the university two years earlier when it was occupied by the IPKF, often staying after curfew to organize repairs to the bomb damage. Eventually her colleagues were persuaded to return by her conviction that ‘we must show a will of our own to make our own future’. In a note to the vice-chancellor the day she returned, she simply stated: ‘There is no life for me apart from my people – so here I am’. The Tigers had perhaps been the best hope the downtrodden Tamils had – the teeth – if not the voice – of the oppressed, the only group to offer effective resistance against genocide. Their appeal in the north and east of the island grew in direct proportion to the barbarity of the Indian and government forces. Rajani was active in exposing and documenting the atrocities, the limbs cut from live youths on saw benches, the crushing of heads under the wheels of armoured vehicles, immersions in acid, rapes and strangulations, the dismembered bodies draped from trees and telegraph poles and the bullet-riddled corpses smouldering on piles of burning tyres by the roadsides. But she became equally concerned with similar excesses by the Tigers and their role in the militarization of the youth, as many of the LTTE’s young idealists died or grew disillusioned and left the country. Together with a handful of colleagues, she set up an affiliation called the University Teachers for Human Rights (UTHR) and its reports were circulated to human rights organizations. A fellow member of the UTHR said: ‘For Rajani, whoever takes a life must be exposed, independent of party feeling. We wanted to show that, in the first place, we valued life.’ Explaining the work of the UTHR, Rajani wrote: ‘Objectivity, the pursuit of truth and critical, honest positions, is crucial for the community, but is a view that could cost many of us our lives. It is undertaken to revitalize a community sinking into a state of oblivion.’ Popular support for the Tigers grew when the IPKF arrived to ‘keep the peace’ in July 1987. Their initials came to stand for ‘Indian People Killing Force’, as they massacred civilians, including those in hospitals and refugee camps, and subcontracted the butchery to bands of anti-Tiger, anti-government Tamil militias. These Indian-trained and armed groups added to the proliferation of paramilitary organizations throughout the island, groups with two things in common: a blind pursuit of murder that made everybody someone’s enemy, and the word ‘Liberation’ in their convoluted titles. When doctors were too frightened to reveal an IPKF massacre at Jaffna Hospital in Octover 1987 which left 70 staff and patients dead, and were even afraid publicly to commemorate their dead colleagues, Rajani interviewed survivors; and from her own experience she wrote: ‘So we lay down quietly under one of the dead bodies, throughout the night. One of the people had a cough and he groaned in the night. One Indian soldier threw a grenade at this man, killing some more persons. In another spot one man got up with his hand up and cried out: ‘We are innocent. We are supporters of Indira Gandhi.’ A grenade was thrown at him. He and his brother next to him died…the blasting grenades made tremendous noises…then the debris and dust would settle on us and cake in the fresh blood of those dead and injured.’ With a handful of other women, Rajani cycled throughout the region, collecting information on the murders and tortures, and on the rapes that are a widespread but shamefully hidden consequence of the conflicts. She listed the experiences of the mothers and young girls, counseling them and giving them whatever they needed from whatever she had. Her father says: ‘Here women cling to their jewels. When Rajani died she had not a single brooch, it had all been given away.’ Rajani tried to mobilize the bereaved and dispossessed, particularly women, to find strength together. She founded a centre where some of the women could begin to rebuild their lives in a self-sufficient community called ‘The Whole Woman’. In the centre you hear something unique in the north of Sri Lanka – women laughing together. Rajani wrote: ‘I want to prove that ordinary women also have enormous courage and power to fight alone and hold our inner selves together. Through this work Rajani came to be regarded as a traitor by the Tigers. Her mother says: ‘They used to say of her, ‘Even when an Indian soldier dies she will cry.’ Now there is news that some of the younger women of the centre have been ‘conscripted’ into the LTTE. In two years of jungle and urban warfare the Tigers claimed the lives of more than 1,500 Indian troops and hundreds of members of the murderous militant groups backed by the IPKF. But they disregarded the fact that many young members of these groups had been ‘conscripted’ at the point of gun. They also massacred their relatives and anyone else who was judged to have ‘cooperated’ with the enemy. After one LTTE ambush in which six Indian troops were killed, the IPKF ran amok in a coastal town, north of Jaffna, killing 51 civilians, including babies, in three days of fire and looting. Medical workers found bodies in the streets, partially eaten by dogs; more than 5,000 people lost their homes. In lines from a letter sent to friends in London, Rajani wrote: ‘You want events, numbers, case histories? Not now please, because my mind is strangled. That is what we live. Pain, agony and fear – always fear. I ask you, could you write straight When people die in lots? When you find them dead like flies. In there, over there, Left on the hospital corridors, to the elements, For the birds and dogs to scavenge. When you bury your neighbours in their own garden, When people – thousands and thousands, Are herded into temples, churches and schools, When the beautiful sandy precinct of the temple Becomes nothing but one whole shit dump, A hell-hole with a teeming mass of people, No one cares for the people, The Government, the Indian army, Not even the Tigers, nor the other movements. Today we are a trapped people, We are made to walk this suicidal trip. Our great brave defenders and freedom fighters Lure the enemy right to our doorstep. To the inside of the hospital, Start a fight, ignite a landmine, Fire from each and every refugee camp, Escape to safety. Tigers have withdrawn, while We, the sacrificial lambs, Drop dead in lots.’ Rajani was murdered on the second day of a ceasefire between the LTTE and the Indian and government forces, on the eve of the Indian army pulling out and the securing of a deal that now effectively gives the Tigers official control over life – and death – in the north of the country. They have been entrusted with dispensing the law because, their political adviser, Anton Balasingham, said: ‘We are armed and talking from a position of strength’. The University Teachers for Human Rights planned to publish a testimony called ‘The Broken Palmyra’ – after a tree that traditionally represents the strength of the Tamil people – and early copies began to circulate underground three months before Rajani’s murder. It questioned the militarization of the youth, the ability of military action alone to bring true liberation, and perhaps helped to seal Rajani’s fate with such statements as: ‘There is no voice for the needs and opinions of the people without guns. There are Tiger murals, Tiger courts, ribbon-cutting by the Tigers, but the people are bystanders, unable to determine the course of their struggle.’ In a letter to a friend in London, which arrived two days after Rajani’s death, she wrote: ‘One day some gun will silence me. And it will not be held by an outsider, but by a son – born in the womb of this very society – from a woman with whom my history is shared.’ Anton Balasingham says the Tigers’ puppet-master, now launched as a legitimate political party called the People’s Front of Liberation Tigers, ‘have yet to iron out and find an autonomous model for the issues of national development, money, education and land’ for the Tamil people. In Jaffna the dispossessed queue all day for a one-off government resettlement payment of 2,000 rupees (about 33 pounds or enough to buy 10 bags of cement). Hundreds of children in the region suffer from cerebral malaria; there is 75 percent malnutrition in children under the age of five. The suicide rate is the highest in the world. When Rajani died, 2,000 people, many of them students and the poor, defied intimidation to walk through Jaffna in a silent show of grief. But such sentiment is now stamped out by 12 year-old boys. At Elephant Pass, the thin strip of land separating the rest of the island from the Jaffna Peninsula, these ‘Lords of the Flies’ make their presence felt as every passing vehicle is checked for ‘the enemy’. Young boys with black hoods, once forced conscripts in one of the anti-Tiger militias, peer through eyeslits and are forced to betray familiar faces with a nod. No one knows how many of the accused are disappearing in the continuous identity parade. Recruiting posters appealing to 14 year-olds assert ‘Tigers Don’t Cry’. LTTE officials maintain that there is a 13 or 14 year-old age limit for political and military training, but one section commander, faithfully recording his troops manoeuvres in a ‘Monitor’s Exercise Book’ with school, date, name and subject spaces on the covfer, was happy to show off the 12 year-old cubs who can strip down a Kalashnikov faster than most children can turn a Biro into a pea-shooter. A shopkeeper tells how he is doing a good trade in some dubious balm for the boys’ feet, blistered by their new boots. He starts to talk with bitterness of his own 13 year-old who has recently joined the ranks, but falls silent as a Tiger pack passes. They are 40 yards away, out of earshot, but he shakes hands and says, ‘Sorry’. A handful of courageous people continue Rajani’s work. But talking to them was a secret affair in places designated with pre-arranged signs by anonymous messengers who passed in the street. One individual, who has already had his life threatened, voices treason when he says: ‘Martyrdom and traitors are key words in the missives of the Tiger leadership. But there can never be peace and welfare for the people when the political philosophy of those in charge comes from the barrel of a gun. We live under the politics of destruction, where future generations are being taught that anyone who questions is a traitor to the cause. An army of pliant children is being cynically gathered to ensure that the doctrine of total compliance has its own momentum.’ For the moment, this small group of people ensures the survival of the question: ‘Who killed Rajani Thiranagama?’ But their voice is a small one in the silence of others, like the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Jaffna, the Right Revd Theoga Pillai, the spiritual shepherd of a 150,000 flock, who says, ‘They say the Indians or someone did it. She was a bit outspoken you know. It is no use complaining – nothing happens. The people know that.’ But what is his own opinion? ‘I don’t have one’, he says. ‘It is best not to. Will you drink your tea.’ When night falls only the children venture on to the streets, in big, awkward boots and army fatigues. With grenades threaded at their waists and assault rifles in their skinny arms they follow a pied piper called the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. It is a liberation that chains every boy with a regulation cyanide capsule on a string around his neck, a freedom fight that has made an enemy of the young women in the picture on the wall. ***** The name spelling of the Archbishop of Jaffna, Merritt’s last interviewee, in the article was rather unconventional. It shows some sloppiness on the part of interviewer. The conventional one was Bastiampillai Deogupillai (1917-2003). His observation and mild comments that Dr. Thiranagama was “a bit outspoken” cannot be faulted. Was this trait of Dr. Thiranagama a handicap for her? An optimal one word that could replace ‘a bit outspoken’ was ‘risky’. Dr. Thiranagama willingly took risks in her life and she was dealt with a bad hand. Brief Comparison between the assassinations of Two Lady Doctors Now, I remind the readers of another assassination that happened nine days before Ms. Thiranagama’s death. Tit-for-Tat killing has been common in Sri Lanka, as elsewhere. This angle has not been touched by those who mourn for Rajani. While re-reading Rohan Gunaratna’s account on the JVP and RAW’s activities during 1987-90 in Sri Lanka, I found the following descriptions somewhat of interest. To quote,

It should not be forgotten that since the early 1980s, S.C. Chandrahasan (a son of Federal Party founder S.J.V.Chelvanayakam) had been one of the beneficiaries of RAW’s funding in Tamil Nadu. His influence there had waxed and waned periodically, depending on which party was in power in Tamil Nadu. Chandrahasan received more benefit during M. Karunanidhi’s tenure as the Chief Minister. And during 1989-90, Karunanidhi had his 3rd stint as the Tamil Nadu chief minister. The somewhat quasi-mirror image symmetry between the assassinations of Dr. Gladys Jayewardene and Dr. Rajani Thiranagama has been ignored by many.

My view is that, with due respect to the Rajani fan club, the LTTE’s opponents cannot ignore the alternate options as well. Couldn’t it be the EPRLF that killed Dr. Thiranagama for recording the misdeeds of their then patron – the IPKF? (see below: after 20 years – two Sinhalese who have some grudge with the LTTE bring out some bones from the closet.) Or couldn’t it be the Sri Lankan military vigilantists (through their hired hands among the Tamils) for recording the misdeeds of the SL army, in addition to trap her husband (a JVPer, living underground and eluding capture) while he visited the funeral of his wife. Proof that Dr. Thiranagama had been harassed by IPKF and Sri Lankan army comes from the victim’s father. What Dr. Thiranagama’s parents failed to note in their interview with John Merritt was the following facts. Rajani was a well known ‘skirt’, albeit a ‘hidden skirt’ in the secretive JVP clique, and she was married to a JVPer, who was living an underground life – hiding from authorities. On top of it, she was also a Tamil doctor-activist. It is not unusual that she would have landed in the files of the GOSL-military intelligence. Read below, for the evidence, that remained hidden for nearly 20 years. How Convincing is the Circulated Grapevine News? Last Year’s Revelations Now, it seems the other shoe has fallen! Rajani’s husband Dayapala Thiranagama, in rebutting the views of raucous polemicist Dayan Jayatilleke posted the following comments to the transCurrents website of D.B.S. Jeyaraj, on October 4, 2009. I quote:

Wow! What a revelation that Dayapala Thiranagama had divulged, after 20 years and placed Dayan Jayatilleka in a spot. This confession by Rajani’s husband fills in a few blank spots. He “left for London in December 1989”, one month after the execution of JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera and his coterie by the SL army. He doesn’t tell the details about how he was able to leave the island and who helped him, if he was living an underground life. Many Sri Lankans know that among the top-ranking JVPers of that time, only Somawansa Amarasinghe was able to escape execution by the SL army, courtesy RAW operatives. In the same website, Dayan Jayatilleka, then rebutted Dayapala Thiranagama, as follows:

In this rebuttal, Dayan Jayatilleka had stated that, at that time he has yet to join the UNP. So, what was his party position then? – still belonging to the Vikalpa Kandayama or allied to Sri Lanka Mahajana Party (of Vijaya Kumaratunga and his wife Chandrika). Note that, he served as a cabinet minister in the North-East provincial council, headed by Varadharaja Perumal, from December 1988 to June 1989. Check his line, “My interlocutor, who may have been Gen Chula Seneviratne…” Jayatilleka was not sure, who provided the information in Sept. 1989 that “it was an EPRLF hit”. Why should an army officer who belongs to the Intelligence section provide complete information to a guy who is not a ‘big wig’ in the then ruling party hierarchy? Again, Jayatilleka states, “It is this that I shared in good faith with Dayapala.” That also indicates that, while Dayapala was living ‘underground’ hiding from the SL army militia, Jayatilleka was ‘keeping in touch’ with Rajani’s husband. To wiggle out from the spot into Dayapala Thiranagama had fixed him, Dayan Jayatilleka in an escape gambit, then cited the inference of anti-LTTE scribe D.B.S. Jeyaraj. Living in Canada, for the past 20 years, Jeyaraj caters to the community of non-Tamils in Sri Lanka and elsewhere who cannot comprehend Tamil. But, the opportunistic swinging of Jeyaraj on Eelam Tamil issues is usually well understood by Tamils who can read, write and speak Tamil. Here is a case of intelligence of Jeyaraj (living in Canada) pitted against the Sri Lankan army’s military intelligence, having headquarters in Colombo, but tentacles all over the island, including Jaffna. Common sense indicates that Jeyaraj’s intelligence cannot be superior to that of Sri Lankan army’s military intelligence; but Jayatilleka’s intelligence, for simple convenience of scoring a brownie point, anoints Jeyaraj as a super sleuth! I can provide a list of Jeyaraj’s hoisted balloons that flopped. Maybe Jayatilleka should be reminded of Occam’s razor principle (aka, law of parsimony), after William of Ockham (c.1285-1349): Pluralitas non est ponenda sine necessitate. In English, it means that, ‘all else being equal, simpler explanations should be preferred over more complex ones.’ Now, tie in the information provided by Rohan Gunaratna, that the escaping JVP cadres (aftermath of the decapitation strike by the GOSL militia in November 1989) were served by S.C. Chandrahasan’s Tamil refugee networking unit in Tamil Nadu via RAW and that Dayapala Thiranagama “left for London in December 1989”. I assume in good faith here that Rohan Gunaratna did interview S.C. Chandrahasan in 1991. Thus, unless Dayapala Thiranagama provides proof that he left for London directly from Katunayake, Sri Lanka in December 1989, he could have been one of these JVP cadres, who moved to Tamil Nadu and later to London, under false pretense. Coda Though what I have pursued here may be uncomfortable to many of the kin, fans and students of Dr. Rajani Thiranagama, I subscribe to the epigram of Einstein, ‘If you are out to describe the truth, leave elegance to the tailor’. References Barbara Crossette: For Sri Lankans, terror strikes from all sides. New York Times, Sept.16, 1989. Rohan Gunaratna: Indian Intervention in Sri Lanka – The role of India’s Intelligence Services, South Asian Network on Conflict Research, Colombo, 1993, pp. 312-313.

| ||||

On 21 September last year she was shot dead while cycling home from Jaffna University, where she was Head of the Anatomy Department. She had just finished marking the last of her students’ final exam papers. Her killer struck at about 6 pm on the quietest spot in her 15-minute journey. He had the time, when she fell after the first shot, to fire four more bullets into Rajani’s head. Two students saw the killer cycle off; they managed to persuade the reluctant driver of a passing car to take her to hospital. But she was dead on arrival, and the students ran away without leaving their names.

On 21 September last year she was shot dead while cycling home from Jaffna University, where she was Head of the Anatomy Department. She had just finished marking the last of her students’ final exam papers. Her killer struck at about 6 pm on the quietest spot in her 15-minute journey. He had the time, when she fell after the first shot, to fire four more bullets into Rajani’s head. Two students saw the killer cycle off; they managed to persuade the reluctant driver of a passing car to take her to hospital. But she was dead on arrival, and the students ran away without leaving their names.