Ilankai Tamil Sangam

Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA

Published by Sangam.org

by Sachi Sri Kantha, April 23, 2011

|

After the military attack on the satyagrahis and the declaration of emergency and curfew on 17th April 1961, and as the strike on the estates started, she spoke and made an appeal to the Sinhalese masses on 26th April 1961. Her speech was as much emotional and inflammatory as she was inexperienced. In that speech she had imputed separatist motives to the Federal Party and sought to avail of it, an excuse to cloud the language issue. In that speech she said:

|

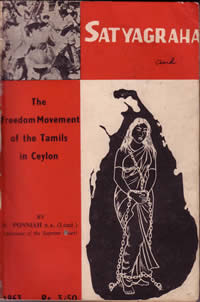

Front Note by Sachi Sri Kantha

One reason I provide the chapters from S. Ponniah’s 1963 book is for those readers in Eelam and the diaspora who were born during February-April 1961 [and have reached 50 years now] in Jaffna and other Tamil dominated districts to realise how lucky they were to be born, survive and live during the first phase of military rule in independent Ceylon, under the SLFP regime. Quite a few were not so fortunate like them.

In last February's installment about the 1961 Satyagraha , I erred when I mentioned that only Chelliah Rajadurai (then the Federal Party MP for Batticaloa) is alive now. What I meant was, only Rajadurai is living among the Federal Party leaders (MPs and would-be MPs such as V. Navaratnam and S. Kathiravelpillai who became MPs later). But, I have overlooked the leading role played by Mrs. Mangayarkarasi Amirthalingam in 1961 in the Women’s Front, and I apologize for this inadvertent error.

|

Tamil girl students in protest march April 1961 |

As Ponniah has not identified the Cabinet members of Sirimavo Bandaranaike, during February-April 1961 when the satyagraha was performed, in his description, I provide the details. Apart from Mrs. Bandaranaike, who also held the portfolio of Minister of Defence and External Affairs, there were nine (eight Sinhalese and one Muslim). Their names are as follows:

Charles Percival de Silva – Minister of Agriculture, Land, Irrigation and Power (also the Leader of the House)

Senator C. Wijesinghe – Minister of Labour and Nationalised Services

Felix Dias Bandaranaike – Minister of Finance

Senator Samuel P.C. Fernando – Minister of Justice

Senator Alexander Perera Jayasuriya – Minister of Health

Tikiri Bandara Ilangaratne – Minister of Commerce, Trade, Food and Shipping

Punchi Banda Gunatilaka Kalugalla – Minister of Transport and Works

Badiuddin Mahmud – Minister of Education and Broadcasting

Maithripala Senanayake – Minister of Industries, Home and Cultural Affairs.

The Army Commander at that time was Major General H.W.G. Wijeyekoon, who held that rank from January 1, 1960 to December 31, 1963.

The dates in April 1961, which deserve recognition are as follows:

April 5, 1961: Sam P.C. Fernando, the Minister of Justice, had talks with S.J.V. Chelvanayakam in Colombo, that lasted for four hours.

April 14, 1961: Mr. Chelvanayakam inaugurated a Federal Party postal service in Jaffna.

April 17, 1961: The Sirimavo Bandaranaike Cabinet met at the ‘Temple Trees’. Military was sent to Jaffna. Emergency declared in Jaffna.

April 18, 1961: Federal Party MPs A. Amirthalingam and V. Dharmalingam were taken into custody under the Emergency Regulations. Military attacked the satyagrahis. Curfew declared for two days (18th and 19th) in Jaffna.

April 20, 1961: Curfew partly lifted, but tension continued.

Following the arrest and detention of Federal Party MPs, leaders and workers (about 90 from North and Eastern provinces) who were taken to Colombo and held in custody at the Army cantonment at Panagoda in Maharagama, the 1961 satyagraha campaign reached a denouement. In the next installment, I’ll provide excerpts from the 1991 memoirs of V.Navaratnam, who provided a retrospect of what happened in 1961 and why the satyagraha campaign of the Federal Party failed to prolong further.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the 1961 Satyagraha campaign of the Federal Party, I have transcribed below

To mark the 50th anniversary of the 1961 Satyagraha campaign of the Federal Party, I have transcribed below

Chapter 15: The Talks

Chapter 16: The People’s Post Office

Chapter 17: Satyagraha vs. Violence

Chapter 18: The ‘Iron Curtain’ – The Hardships

Chapter 19: The Curfew, Military and People

Chapter 20: The Tamil Question and The Ceylon Indian Tamils

Chapter 21: Why Not the Federal System?

from S. Ponniah’s Satyagraha and The Freedom Movement of the Tamils in Ceylon (1963) book. These chapters cover the events of April 1961. The subtitles, within each chapter, are as in the original.

Chapter 15: The Talks (pp.135-144)

On the day of her departure to London for the Commonwealth Premiers’ Conference, the prime minister promised in her broadcast to the nation that she would settle the language issue on her return from the Conference. The country had earnestly hoped things would improve, communal problems disappear and an era of construction dawn.

The prime minister returned to Ceylon after three long weeks – a period considered by all as too long for a prime minister to stay away while the government and the country were facing a major crisis within its borders. On the undertaking given by the prime minister to settle the language dispute on her return from the conference, the Federal Party decided not to intensify the satyagraha campaign in her absence. The Party also indicated its willingness to negotiate a settlement. In this context, the responsible sections of the country wished and endeavoured to bring together the government and the Federal Party and initiate them for talks. But the prime minister’s speech of March 25th after her return and her indifference towards the proposed settlement of the language issue chilled their efforts. Some professors and men of learning, who had grown up in the best of traditions and culture, were highly critical of the prime minister on account of her failure to honour her promise to settle the language dispute, and urged on her to invite the Federal Party for talks without insisting on the withdrawal of the satyagraha campaign. They also pointed out that talks were possible while the satyagraha was on. Even newspapers of international repute like the London Times, The Hindu and Manchester Guardian had condemned in no uncertain terms the attitude of the government towards the language question. The London Times of April 1st commented as follows:

“The battle is now over the use of Sinhalese in the Courts and the government offices in Tamil-speaking provinces. This is a very different matter from the debate at the national level which was conducted by highly educated Tamils. In the Northern and Eastern provinces, the ordinary Tamil speaks no language but Tamil, and may not even read that. The question remains who should make the first move. It should surely be from the government side. It is Tamil confidence that had been shaken by the events of the past forty years and Ceylon has suffered thereby.”

A similar suggestion was made by the Hindu. Its editorial dated 13th March ran as follows: [dots, as in the original.]

“Sinhalese and Tamil observers alike have testified to the closing of the Tamils’ ranks and their grim resolve to stand up to the bitter end. But credit must be given to the Federal Party leaders for their decision not to launch civil disobedience during the prime minister’s recent absence from the country. It was hoped that Mrs. Bandaranaike would make a suitable response to this gesture but her broadcast on her return was by no means couched in the language of conciliation. While she held out hopes of making some little adjustments here and there in the implementation of the ‘Sinhala Only Act’, she would not concede what her husband, when prime minister, had conceded; viz. that Tamil would be recognized officially as the language of a national minority and that provision would be made for its reasonable use in official business. And instead of inviting the Tamil leaders straightaway to conference to evolve a working agreement for the future, she harped again on the recent past and insisted on the Tamil leaders publicly repudiating satyagraha before she would have any dealings with them…The prime minister’s speeches seemed more designed to win Sinhalese votes than to carry conviction to the Tamils.

That is why it now appears proper that the prime minister of Ceylon should lay aside ideas of false prestige, call to the Tamil leaders into consultation and work out an acceptable settlement…Both parties should remember that their lot is cast together in Ceylon, that civil commotion would spell the doom of her plans for development on which both were keen and that it would take years for the scars left by such strife to disappear.”

The prime minister and her government could not do otherwise than seem to bend a little before this spate of criticism. The government, then called upon the Minister of Justice to have ‘informal talks’ with the Federal leaders. This minister dispatched a special plane from Colombo to Jaffna to fetch Mr. Chelvanayakam for talks. Mr. Chelvanayakam, who was then convalescing from an attack of influenza, readily responded to this invitation, left his sick bed and flew to Colombo. Mr. Chelvanayakam was accompanied by some Federal Party MPs, Mr. S.M. Rasamanickam MP for Padiruppu, too attended the talks. It must however be observed that it was a grave omission that the Federal Party did not invite MPs outside the Federal Party to join the talks with the Minister.

|

Satyagraha participants from Valvettithurai April 1961 |

On 5th April, Wednesday night the Minister of Justice with Mr. Chelvanayakam had talks. The talks lasted for nearly four hours. Immediately after the talks, on the same day, all the Federal Members of Parliament except Mr. Chelvanayakam, left their respective provinces. All of them expressed the same view that the talks were not at all hopeful. It was learnt that the Minister appeared to be a man ‘on pins’. As he walked into the venue of the talks, he was said to have remarked, “Well, Mr. Chelvanayakam, unless you are prepared to relent, we cannot be expected to do anything in the matter!” Immediately Mr. Chelvanayakam retorted: “Well. That is what we expect of you now.” Mr. Chelvanayakam urged the following five minimum demands:

Mr. Chelvanayakam who had flown to Colombo inspite of his ill-health, had intended to make use of the opportunity and find a speedy and satisfactory solution to the language problem. With this end in view, he was, in the course of the talks, at great pains to convince the Minister that the Tamil speaking community would be placed under a grave hardship if its basic rights, viz. language rights, etc were denied. But it appeared that the Minister’s impatience and intransigence served as a bar against any understanding or settlement. Though purporting to satisfy the public and press criticism by initiating talks on the language issue, the government however lacked sincerity of purpose and by this the government knocked out the bottom on this basis of which alone talks could have succeeded and a settlement arrived at. Thus the government deliberately side-stepped public opinion that demanded a settlement. What both sides had discussed have been substantially and briefly embodied in the Minister’s report. For the information of the readers, the report is set out here in full.

Chelvanayakam- Justice Minister Talks

The Minister’s Report

(1) Language of Administration in the North and East

Mr. Chelvanayakam and the others present were insistent that for all administrative purposes Tamil should be the language in these areas. The Federal leaders stated that they would not accept official records i.e. including minutes and files being maintained in any language other than Tamil, though of course they would have no objection to a translation being kept in Sinhalese, if the government so desired. According to them, it would not be sufficient for the government to recognize only the right of the Tamil speaking inhabitants of these areas to transact their business with the government in the Tamil language.

They were emphatic in their demand and that the official records in these places should be kept in the Tamil language. They further stated that correspondence between, for example, the government agent, Jaffna, and the Home Ministry should be in the Tamil language. They agreed that this could not be done without an amendment to the Tamil Language (Special Provision) Act and stated that the government should make the necessary amendment to that.

I informed Mr. Chelvanayakam that if there were any matters which were not covered by the regulations made by me under this Act and presented to parliament, I would accept any regulations which may be prepared by them and which would not be inconsistent with the Provision of the Tamil Language (Special Provision) Act. This does not satisfy them as their demands extends to all administrative purposes without exception or qualification and includes the records being maintained in Tamil.

I pointed out that if their view was accepted there would be no place for the use of Sinhalese as the official language in practice in these areas. Mr. Chelvanayakam stressed that this point was fundamental.

(2) Language of the Courts

(a) As regards the language of the Courts, Mr. Chelvanayakam stated that this too forms the part of the administration. He, therefore, stated that the language of the Courts in the North and East should be restricted to the Tamil language. I asked Mr Chelvanayakam whether in order to maintain Sinhala as the official language it would be possible to make some arrangement whereby a simultaneous record in the courts in Sinhala and Tamil may be maintained in the North and East however inconvenient that might be. Mr. Chelvanayakam thought it would be impracticable.

(b) With regard to cases that go up in appeal, Mr. Chelvanayakam stated that one solution would be to establish a panel of Supreme Court judges who would deal with the cases from ‘Tamil’ Courts in that language. He said that he would favour this solution. The second solution he said would be to provide a translation in Sinhala for the use of the Appeal Court, which course he did not favour.

(c) Mr. Chelvanayakam emphasized that as a necessary corollary to Tamil being declared the language of the Courts, all laws and regulations would have to be passed in Tamil also in parliament. I asked Mr. Chelvanyakam whether it would not be sufficient to have a Tamil translation of laws that may be enacted by parliament in Sinhala. Mr. Chelvanayakam was not agreeable to this.

Mr Chelvanayakam stated the government should agree to the language of the Courts bill and other laws being amended for the purpose set out above.

(3) Regional Councils

According to Mr. Chelvanayakam, Mr. Bandaranaike had in mind the establishment of Regional Councils all over the island and a draft bill had been prepared. The Federal Party had at that time urged that Regional Councils should have greater powers and their demands had been embodied in the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact. Mr. Chelvanayakam, therefore stated that the government should agree to the establishment of regional councils as contemplated in the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact and also in accordance with the draft presented by the Federal Party to the government a few months ago.

I asked Mr. Chelvanayakam whether the consideration of this matter could not be postponed for some time. He answered that if the government accepted the principle on the lines indicated by him he would be willing to defer the actual implementation for about three months.

(4) The Language Rights of Tamil speaking persons outside the Northern and Eastern Provinces

Mr. Chelvanayakam contended that a Tamil speaking person in any place other than the North and East was entitled to correspond and transact his business with the government department in his own language. I informed Mr. Chelvanayakam that the Cabinet had directed in December 1960 that a letter received in Tamil should be replied to with a Tamil translation and that a directive had also been given that forms to be used by the public should be in all three languages in all parts of the island. I asked that any inconvenience caused by non-compliance with these directives during the transitional stage be not taken into account.

(5) Rights of Tamil Public Servants

Mr. Chelvanayakam stated that all entrants, i.e. those who entered the Public Service prior to 1956 should not be put into any inconvenience by reason of the fact that they did not know Sinhala. He stated that if they were unable to learn Sinhala they should be permitted to retire with compensation. I stated that the Cabinet had directed that any Public Servant who counts over ten years of service could retire with five years added to actual service.

Mr. Chelvanayakam had no further comments to make on this. Mr. Chelvanayakam agreed that as regards new entrants they should comply with the law in regard to the official language and any directives given in regard to proficiency in the official language. He also pointed out that in regard to certain public officers (e.g. teachers in Tamil medium schools who are transferable only to another Tamil mediuam schools) there was no necessity to acquire proficiency in Sinhala.

Postscript from Mr. Chelvanayakam

Mr. Chelvanayakam has written to the Minister of Justice on 14.4.1961, as follows:

“The report containing 2 pages of foolscap covering 4 hours of talk had necessarily to be brief summary of what took place. As you were personally presenting it to the Cabinet and as the report was correct in substance so far as it went I signed the document.

Had the document been put to me as a statement to be released to the public I would have wished to make certain points fuller. In particular, I would have made the following alterations.

When the prime minister returned from the Conference a group of Sri Lanka Freedom Party members told her that the cause of the satyagraha according to popular view was the Language of the Courts Act and that it needed amendment urgently. When this fact was intimated to the Justice Minister, he was understood to have said that he would rather resign his membership of the party than alter a syllable of the Act. It was the same minister who was reported to have described the Tamils as the ‘traditional enemies’ of the Sinhalese. When it was divulged there would be talks between the Justice Minister and Mr. Chelvanayakam, a man among the vast crowds at the Jaffna kachcheri exclaimed, “What! Of all the ministers, talks with the Justic Minister!” It was no surprise that the talks failed. Though professing to follow the language policy of the late prime minister Mr. S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, the present prime minister and her government did not pursue his policy. Mr. A.C. Nadarajah, a former Vice-President of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party revealed to the public that the language subcommittee under the chairmanship of Mr. S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike passed the following resolutions in September 1955, with regard to the use of Tamil in the island.

“Besides making Sinhalese as the official language of Ceylon, due recognition must be given to Tamil and for this purpose legislation must be passed. This policy was enunciated by Mr. S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike in this way:

*****

Chapter 16: The People’s Post Office (pp.144-147)

The talks failed and the Tamil speaking people became disappointed, having fervently hoped for a satisfactory settlement. They also realized that the government was not keen enough to protect their rights, however reasonable and fundamental they were. Mr. Chelvanayakam presiding over a mass meeting at the Jaffna esplanade on 12th April, a few days after the talks had failed, said:

“As the political parties in south Ceylon treat the Tamil question as a suitable issue to play upon the emotions of the Sinhalese voters and enthrone themselves on the seat of power, these parties or their politicians refuse or are unable to see the justice of our demands.”

The Tamil-speaking people felt themselves humiliated. Naturally, they decided there was no alternative but to strengthen the resistance movement. Although public opinion in the North and East was otherwise, the Federal Party halted the

intensification of the satyagraha campaign during the absence of the prime minister who had left for the London conference, a step that was much lauded by world newspapers like the Hindu. Now with the failure of the talks the Federal Party had to yield to the wishes of the Tamil speaking people. Thus by way of intensifying the campaign, the ‘Tamil Arasu (Federal Party) Postal Service’ was inaugurated by Mr. S.J.V. Chelvanayakam on 14th April 1961. This day at 12 noon the satyagrahis stood up as usual and were in silent prayer for two minutes before they sat down again. Immediately thereafter, the postal service was started in the Pension Branch opposite to the main kachcheri building in breach of the Postal laws, as an act of civil disobedience. This momentous occasion was witnessed by nearly 10,000 people although the exact time of the inauguration was not intimated to the public. The queue of people who had waited to purchase the Tamil Arasu stamps extended to such a length that it winded into streets and lanes. The people cheered the leader Mr. Chelvanayakam, as he got into the post office counter dressed in all pure white national dress. The post office sold out 2,500 stamps, 2,500 stamped envelopes and 3,000 postcards, in a little more than an hour. This sale in that brief period far exceeded any other sale of stamps in such a period in the history of the island’s postal service. Thousands went away disappointed, not being able to purchase any more stamps. The Federal Party for very good reasons, had limited its first sale.

|

Women satyagrahis outside Jaffna Kachcheri April 1961 |

The office had the general look of a post office. On the wall was written ‘Tamil Arasu Postal Service’. Close to the wall there was a letter box, all painted in bright red. On it was written in Tamil ‘Tamil Arasu Post Box’. Across the upper part of Mr. Chelvanayakam’s national dress was written in green ‘Tamil Arasu Postal Authority’. When this service was being inaugurated thousands of Tamil speaking people mobbed the post office and acclaimed it at the top of their voice – “It is our post office. It is the People’s Post Office.”

Mr. Shivasundaram, Member of Parliament, in a letter written by him to the Superintendent of Post and Telegraphs, Jaffna, informed him that the Federal Party had started a postal service of its own. The envelope carried on it Tamil words which meant “Tamil Arasu Postal Service”. This letter was delivered by Mr. A. Amirthalingam, MP. A similar letter was handed over to the Superintendent of Police by Mr. M. Sivasithamparam, MP. These two members of parliament, styled themselves as postal peons, and set out to deliver them by motor cycles.

A letter to the government agent was also sent by Mrs. Amirthalingam. By that letter she complained that the government had planned to starve the Tamil speaking people of Jaffna and subjugate them by denying them rice rations. She further pointed out that even the women folk were prepared to die of starvation in the course of their just struggle for their basic rights without ignominious surrender. This letter was delivered to the government agent by the ‘peon’, Mr. V. Dharmalingam, MP. Tamil Arasu Post Boxes were placed at the Federal Party office and in front of St. John’s College, Jaffna.

An Englishman and his wife visited Jaffna and they took particular care to be present at the opening of the Tamil Arasu Postal Service. They purchased stamps, stamped envelopes and postcards to the value of Rs. 50/. They appeared to be quite happy in the midst of the satyagrahis. The Englishman was heard to say to a group of satyagrahis:

“We have seen with our own eyes the satyagraha you are performing in defence of your just rights against heavy odds such as the burning heat of the Sun and rain, fasting and praying, toiling and suffering. But I am certain that if there is justice in any part of this country, it will hear you. May God bless you.!”

Again on 17th April, Mr. Chelvanayakam inaugurated a Federal Party postal service at Kankesanthurai. Altogether twelve post offices were opened in the Kankesanthurai electorate. Everywhere the opening of the postal service attracted vast crowds who shouted slogans wishing long duration of the service. Mr. S. Nadarajah, proctor of the Supreme Court and a leading member of the Federal Party, was the postmaster general.

*****

Chapter 17: Satyagraha vs Violence (pp.148-156)

On the morning of 17th April (Monday) 1961, the Ministers met at ‘Temple Trees’ and discussed for three to four hours the situation in the Northern and Eastern provinces. At this meeting the question of imposing a state of emergency under the provision of the amended Public Security Ordinance in the satyagraha affected areas was, chiefly, discussed. At no time did the Inspector General of Police report to the government that he was unable to maintain law and order in any part of the island. The only reason given by some of the ministers was that the resistance in the North and East had developed into a movement for separation.

The more sober members of the Cabinet, however, observed that it would be an insult to the intelligence of the Cabinet to construe federation as separation. These Ministers expressed surprise at the idea of declaring a state of emergency in the satyagraha affected areas where there was a marked degree of peace and tranquility – a spectacle that had softened the hearts of all visitors. But the more dominating section of the Cabinet prevailed over and coerced them into agreement.

Following the decision to impose a state of emergency, the Minister of Finance and Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Defence and External Affairs, Mr. Felix D. Bandaranaike held a series of conference with army, navy and police chiefs. Consequent on these conferences a special train carrying about 350 soldiers and 15 officers left for Jaffna from [Colombo] Fort station at 6 pm on the same day (17th April). The troops consisted of two contingents, one of which called the Sinha Regiment comprising only Sinhalese soldiers. The special train reached Jaffna at about 2:30 am, following day. These troops went into the kachcheri by the back door and joined troops who were already there. Earlier, the troops were sent by road to the North and East.

Immediately after the arrival of the new troops, all the troops were seen crowding in the kachcheri premises between 2.30 am and 3.00 am. It was one of the unwary moments of the satyagrahis! There were only a few of them, about 200 of whom women counted more than 90. The day’s burning heat of the Sun, the fasting, constant prayers and singing of hymns had given them a tired feeling; and the bleak weather of the chilly midnight had dragged them almost into a slumber. There were hardly any spectators at that time of the weary night. A number of young and sick men who performed satyagraha at the Old Park entrance had fallen asleep. But at the Main entrance, the women satyagrahis were, comparatively, more alert and some of them were still humming devotional songs. As against them, there wee about 600 army men carrying rifles, bayonets and clubs.

Certain of the police officers came forward and told Messers V. Dharmalingam, MP and A. Amirthalingam, MP, that they had been instructed to take them into custody under the Emergency regulations. The two leaders replied that if it was the order of the government to arrest them, they would not resist arrest. At once, these two Members of Parliament were arrested. Immediately thereafter, Mrs. A. Amirthalingam was taken into custody. Then the entire army fell on the innocent and peaceful satyagrahis like wolves on the fold and brutally attacked them with belts, rifle-butts and clubs as they were then not fully awake. With a terrible shock, the sleeping satyagrahis woke up screaming and groaning for help. They were bleeding from their heads, noses, chests and other parts of their bodies.

The army trampled on them pell-mell. A number of satyagrahis had their legs broken; some of them were struggling for breath, having been trampled on their chests and abdomen. A teenage boy was standing close to the wall of the Old Park entrance when a soldier suddenly struck him on the head with the rifle butt. The boy fell instantly on the ground and without a pause the soldier, with his boots trampled on the boy’s abdomen and chest with such brute force that the boy cried aloud for mercy. Even as he did so, the soldier kicked him violently on his right hips with his boots. The boy groaned, panting and struggling for breath. There had been many cases of this type. Even in the face of such merciless violence most of the satyagrahis sat still with folded arms bleeing on all sides of their bodies. Then the army dragged them, booted them and rolled them away from the precincts of the Residency gates in that helpless dark night.

There was an aged man, subject to rheumatism, performing satyagraha at the Old Park entrance, where the attack first started. In the thick of the maze, this rheumatic person attempted to get up. But the rheumatic stiffness and pain was so acute having sat there for a long time, that he held his buttock muscles with his hands to massage them. As he was in that position, a soldier kicked him with his boots on the buttocks and as the man shouted ‘aiyo’ (alas!), he struck his head with his rifle-butt. This sent the man reeling on the ground groaning for help. Even then the soldier did not spare him but pursued him and pulled him by his hair and dragged him until he was almost senseless. There was a middle aged man holding his bicycle a few yards away from the thick of the incidents. Seeing them he was so lost that he did not think of making good his escape. A soldier rushed at him and told him to get on to his bicycle which that man did. As he begun to pedal, the soldier tripped him with his boots violently and as the cyclist fell, he dealt a severe blow on his head with his rifle-butt and he fell from his bicycle.

Amidst such brutal violence, still some of the satyagrahis sat gallantly without a stir waiting only to be attacked. Even the natural instinct of raising one’s own arms or limbs in self defence did not prevail over the studied sufferance and discipline which was the most noteworthy feature of the whole movement.

Again with a sudden swoop soldiers came upon the satyagrahis and again the breaking of heads and limbs could be heard at a distance. Their screams and groans too, were heard. A soldier struck a heavy blow with his rifle butt on the head of a young man called Palani of Kalviankadu, and as he fell prostrate, the soldier trampled on his abdomen and chest a number of times. Amidst groans, he sank into unconsciousness. One of those attacked was a Thinakaran and Daily News correspondent. One Navaratnam, a teacher, was severely assaulted on his face with a heavy buckled belt, by a soldier. In consequence, his nose was torn and the torn flesh was seen hanging. Two or three soldiers set upon Mr. S. Nadarajah, proctor and one of the joint secretaries of the Federal Party. He sustained severe head and shoulder injuries. His clothes were drenched in blood. Finally the satyagrahis were dragged, carried and driven away from the precincts of the Residency gates.

As the soldiers were rushing at the women satyagrahis who were sitting at the Main entrance, a group of young satyagrahis intervened between the women and the soldiers to prevent assault on them. The satyagrahis just stood between them without stretching even their hands on the soldiers, who thereupon attacked them and wounded them. One of these satyagrahis was Mr. M. Sivasithamparam, MP for Udupiddy. A strapper himself, he stood on the way of the soldiers with both his arms stretched out horizontally. He was attacked by a number of them. He lost his balance and fell on the ground. He sustained injuries on his face, shoulders and arms. He was unable to use his arms for days together thereafter. The timely intervention of a high-ranking military officer saved the women from being assaulted. It was learnt later, that a few women too were attacked, but it cannot be said with certainty.

It was with vengeance that the army attacked the Federal Party Post Office and hauled it down without even a trace. The military also displayed ability in destroying and burning really inanimate objects like bicycles, cars, boxes and mats. Several cars that were parked opposite to the kachcheri premises were rammed and rendered unfit for use. Their tires were ripped and torn by bayonets. The doors and shutters had been smashed and things inside ransacked.

News of this ravage spread like wild fire. Both the city and its suburbs became astir. In about half an hour thousands of Tamil speaking people were surging on the kachcheri. The crowds were turning almost into a mob shouting ‘violence must be met with violence’. ‘What is the alternative then, if peaceful methods have failed?’, inquired some of them. Students began to assemble in large numbers and discussed what steps should be taken to meet the violence of the armed forces. The students insisted on rushing forward to break the military cordon with all the available means at their command. But the more responsible section of the crowd including certain Federal supporters appealed to them not to plunge the peninsula into chaos, but to watch developments. Almost at the same time, some Federal leaders divulged the news that emergency had been declared by the government the previous night, i.e. 17th April and that the military had been mobilized into action. These leaders made a fervent appeal to the students and the crowds to keep calm and await directions from the Federal Party. They also emphasized that whatever counter move they would make, it must be a concerted one rather an individual and isolated one. They further pointed out “Civil government has failed and military rule established. To this extent our satyagraha is a success.” “Of course! But what are we to do now?” demanded some of the students. In reply they said, “The occasion calls for calmness. The cause is not lost and we must wait for the opportunity”. Then the crowds and the students retraced their steps amidst slogans. “Long live Ahimsa (nonviolence)! Down with tyranny! Long live Justice!”

Those who sustained minor injuries managed to walk to the hospital which was about a mile and a half away from the kachcheri. Those who sustained grievous injuries and who were outside the military cordon were taken to the hospital, in private cars. Inside the cordon, there were some satyagrahis seriously injured and lying there either unconscious or unable to get up. While these injured persons were lying, the soldiers were rollicking and frolicking unconcerned at all with their sufferings.

A little later, the army brought military trucks to transport the women satyagrahis who were still performing satyagraha at the Main entrance unruffled by the terrible happenings and who would not leave the place. But the army would not use these trucks to transport to the hospital, the injured persons who were lying unconscious inside the military cordon. Nor would they allow any private cars to be brought to the spot to remove them. Hospital authorities were rather hesitant in sending out any ambulance to bring those injured persons. Mr. Thurairajasingam, a member of the Jaffna Municipal Council, and the author had to approach a number of higher-up in the hospital before it was decided to send out ambulances to fetch the injured satyagrahis. Nearly a hundred satyagrahis were admitted to the Jaffna hospital for treatment.

The families, relations, friends and sympathizers of the injured persons crowded the hospital. A middle-aged man was suffering from unbearable pain in his hips and thighs and was unable to sit or lie down with ease. He said that as he was seated at the kachcheri entrance, two soldiers lifted him and threw him on the ground. On medical examination it was revealed that a thigh bone had been fractured and muscles turn. As the satyagrahis lay in the wards and verandahs some lying unconscious, some bleeding, some groaning with pain, and others struggling for breath, feelings began to run high. “Are we to show any loyalty to this government hereafter? Hasn’t the government forfeited the right to govern us?” The people spoke in this vein as they were severely ruffled by what has happened.

In history, we have known of the booming of cannons, of massacres, the guillotine and the concentration camps of the Gestapo. These events may far excel the events of Jaffna in their magnitude, but nothing is comparable to the episode at Jaffna in respect of the soldiers’ downright cowardliness! A woman satyagrahi who witnessed the military attack on the unarmed satyagrahis who sat with folded arms, the attack on inanimate objects like bicycles, cars and boutiques, exclaimed – “What bravery is this! Is this anything different from a brutal man, under the influence of intoxication, seizing his own innocent, sweet-smiling babe from its cradle and dashing its brains out on the floor!”

This brave feat appears to have been the personal achievement of the Minister of Finance and Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Defence and External Affairs, Mr. Felix Dias Bandaranaike. This minister failed to understand that satyagraha was a weapon of moral force intended to make those who were in power and in a position of responsibility to realise the justice of the cause of those who want peace and abhor violence and who wish to make them realise so much realization by their own suffering and nonviolent non-cooperation. When the people denounced the police violence on the satyagrahis on 20th February 1961, this Minister was the only person who stood up in parliament and said that the police action was correct and therefore justifiable! From available data it was clear that it was this Minister who precipitated the crisis resulting in the army atrocities on the satyagrahis in the early, dark and solitary hours of 18th April 1961.

Speaking on the Emergency on 3rd May 1961, Dr. N.M. Perera, MP said:

“In a sense this is an unfortunate debate because the villain of the peace is not here – the Hon. Minister of Finance. If there is one person responsible for the major damage on this issue (Language), it is that individual who is concerned and who should have been here today to answer.”

In the absence of this minister from Ceylon, the more experienced and enlightened section of the Cabinet chose note to use violence against nonviolent satyagraha that was being conducted peacefully even under trying conditions of unbearable heat, rain, fasting and prayer that had softened the hearts of all. At least the sense of shame that had been awakened in them by the earlier cowardly attack on the satyagrahis by the police had impelled them to decide not to use further violence on them. But the Finance Minister, whom the author had known so well and whom the author thought to have been brought up in liberal traditions, on his return to Ceylon in a demon-like fashion, took the leap and dared to inflict violence on the peaceful satyagrahis! Even Macbeth would not touch the unguarded Duncan. Lady Macbeth encouraged him,

“But screw your courage to the sticking place and we will not fail. When Duncan is asleep….What cannot you and I perform upon the unguarded Duncan?” [dots, as in the original]

The Finance Minister, in Lady Macbeth fashion, ordered the army to strike the unguarded satyagrahis most of whom were half asleep and half awake in the weary moments of the night.

‘Literacy is not education and education is not culture’. There is no use in traversing heaps of books or glibly dabbling in high sounding words and phrases or man travelling about the air or even going beyond into space and trying to hoist a flag on the moon unless they enable man to mould a heart for the world. We must try to look within us and discover that which is immortal, of everlasting interest and value that pleasant bond of love that can tie the whole world into one family and take it to its bosom of sweetness and heavenliness.

*****

Chapter 18: The ‘Iron Curtain’- The Hardships (pp.157-164)

Means of communications disorganized

While the people in the city of Jaffna and its suburbs were stirred and as they were discussing the situation, it was revealed that the telegraphic and telephone communications from Jaffna to the other provinces were cut off. In the Northern province itself no trunk calls could be taken. Within the municipal limits even Members of Parliament had their telephone connections cut off. No telegrams, no telephone calls could be sent to Colombo and other places. Later it became clear that the government had ordered the main telephone wires to be cut before the armed forces started the attack on the satyagrahis.

Passengers

Hundreds of passengers including government servants had gone to the railway stations in the Jaffna district to catch the Yal Devi, bound for Colombo. Suddenly they were told by the station master that the train service between Jaffna and other places had been completely stopped on the orders of the government. Most of the passengers returned homewards disappointed. Many of them had important engagements in several parts of the country. Several students had to sit for examinations and others to present themselves at interviews. A student in humble and distressing circumstances shed tears that he was prevented from going for an interview. He was the eldest boy in a family of seven children, five of whom were girls. His father died several years ago and he seemed to have developed a sense of responsibility to his family and this misfortune made him more miserable. There were several others placed in the same predicament. That unfortunate boy and some others tried their best to travel by air. They immediately rushed to the Air Ceylon booking office, 1st Cross Street, Jaffna.. They were promptly told that air service had been cancelled. They made efforts to leave for Colombo by some conveyance or other. But by dawn, the movement of troops became massive within the municipal limits and in consequence the movement of civilians and private vehicles became sparing. Bus service also had been stopped.

Suddenly Jaffna found that it had become an isolated place completely cut off from the rest of the world. With the postal service, telegraphic and telephone communications fully disorganized with the train, bus and air services suspended, the external communications cut off and a general black out and curfew imposed, Jaffna was plunged in utter darkness and isolation, devoid of light, freedom and freshness of life. News of any kind could not be sent out of or received in Jaffna.

For very important functions in the whole of Jaffna, people from outside were expected. Many funerals took place without their dearest kith and kin attending them. In respect of one funeral, it was learnt, the only son who was an officer in Colombo, could not come to Jaffna to perform his last rites to his dead father. A mother who was seriously ill and about the pass away was anxiously awaiting the arrival of her only son from Colombo tohave her last look on him but had to pass away with her son still in Colombo making frantic efforts to travel down to Jaffna to see his mother. After two days curfew, only on the third day he arrived at Jaffna by the first train from Colombo. On learning at the railway station that his mother was dead and cremated, he staggered and stood like a statue; then tears were running down his cheeks and in a nervous condition he had to be helped into a car that took him home. Besides, several weddings were either postponed or upset. Would be bridegrooms who were anxiously expected could not come for solemnization.

Several parents in Jaffna had been written to by their sons and daughters studying in India that they were travelling back home for the vacation. The students in India came as far as Dhanushkodi and found that they were denied entry into Ceylon for the government of Ceylon had already cut off all means of communication from Dhanushkodi to Ceylon. Thereby hundreds of young girls and boys were stranded on that side of Palk Strait. Some had already come to Mannar but were unable to come to Jaffna for want of train or bus service. The parents at this end of their journey were running from railway stations to airport and from airport to bus stands in their anxiety to meet their daughters. But none came. For obvious reasons these parents had no peace of mind. Every hour they had to listen to the radio to learn whether there was a possibility of their children coming home. Their excitement was immense. When one of such parents met his daughter at the Jaffna airport after three days of the due date he shed tears of joy. ‘I feared, daughter you were stranded somewhere.’, inquired the father in a perturbed manner. ‘Yes father, we were quite at sea when we learnt at Dhanushkodi that the Ceylon government had closed Ceylon to external traffic’, she replied with a flurried look and tears coming into her eyes. ‘Dhanushkodi was new to me and to the girl companion who travelled with me. After a good deal of nervous rambling we managed to get accommodation in a house. For two days we were in high tension.’

A Dark Chapter

No communication of any kind could be sent from Ceylon to any foreign country. Newspapers, periodicals, pamphlets or even letters were not allowed to be sent abroad; nor were those of the foreign countries allowed to be brought into Ceylon. Only the government communiqués were released to the foreign countries. But these communiqués did not help these countries to know the real situation in the Tamil provinces. The atrocities inflicted on the peaceful satyagrahis and the Tamil speaking people are, still, a dark and mysterious chapter that requires unraveling. Even within the borders of Ceylon outside the Tamil provinces, the people did not know for many days, on account of the curfew and the disorganization of the postal, telegraphic and telephone services, the real happenings in these two provinces. Relations could not see relations; friends could not see friends; government servants and business people could not leave their homes. The towns, streets and lanes were deserted and devoic of civilian population except the military jeeps, trucks and vans that were plying at terrific speed and noisily to and fro.

Sick People

The hardest hit persons were the sick people. At 11 pm on Wednesday, when the curfew was on, a child twelve years of age developed fits. At that curfew hour it was a deadly thing to get out of the house in search of a doctor. There was no doctor in the village. The mother was in tears. The father however dared to go out. While the child was being ton by spasms of epilepsy, the father was winding his way for a car. A quarter of a mile away he managed to get into a cabman’s house. The cabman heard him and he became softened too. But the problem was to drive out. He had no pass and the police station was three miles away. Even with a pass to drive out in the curfew was risky – probably the soldiers would shoot before the pass is shown! But the cabman, however, had a good deal of the human element in him and without any pause, he swung open the garage gate. As he was opening it, alas he heard a heavy stir of vehicles at a distance. And he closed the gate and kept himself inside. He saw three military trucks filled with soldiers. It was a deadly sight! Now the wife and children of the cabman intervened and he, much against his willing mind, had to abandon the idea of driving out at that deadly hour. He, however, promised to take the child to the doctor the very moment the curfew ended at 6 am the following morning. The father of the child, then, tried other cabmen and all of them answered him with blunt refusal. He returned home broken hearted. He and his wife tried their own treatment to improve the child. But in vain. The child’s condition worsened. Like a madman, the father rushed to the house of the Member of Parliament which was about half a mile away in the hope of getting some help to take the child to a doctor. The Member was not there. He then ran to the village headman to get a permit for what it was worth. He promptly gave one but no cabman would trust it. ‘Please help my child’, he cried to every cabman. But no cabman was prepared. The father’s heart sank.

When he went back home it was 3 am, with 3 more hours for the day’s curfew to end. Sharp at 6 am, as the curfew ended the cabman whom the child’s father first approached drove in and indicated his mind to take the child to a doctor. In ten minutes they were with a doctor whose examination revealed that coma had set in. The mother of the child told the doctor that the child had fits about 12 times during the night. ‘Why didn’t you bring the child at once?’ the doctor shouted staring at the parents. When he was reminded of the curfew, he exclaimed, ‘Oh, of course, a curse!’ He did what he could for the child and told them to bring the child again if it survived six hours. After a lapse of two hours the child passed away.

Many cases of confinement [pregnancy] suffered terribly. The women could not be taken to hospitals. Their delivery had to take place in their own homes. In the case of one womn, there was a rupture, although the child was delivered, the bleeding would not stop for some time. An ayurvedic doctor had to be rushed in by the back door in breach of the curfew. Luck, however, favoured her and the physician managed to stop the bleeding. But that bleeding had considerably weakened her. Another confinement was an instrument case. Delivery could not take place at home. During the curfew hours no one was prepared to lend his car. On account of the delay caused, the woman was subjected to enormous suffering. Only after curfew ended she could be taken to the hospital where she was operated on although belatedly. The baby died, but she was saved with immense difficulty. Hundreds and hundreds of sick people suffered hardships on account of the emergency and curfew.

The government interfered on a colossal degree with the liberties of the Tamil speaking people and their freedom of movement. They were not even allowed petrol for their cars or other vehicles to the extent of their requirements. The issue of petrol was made on permits given by the Cooordinating Officer for Jaffna. Considerable difficulty had to be encountered in obtaining the permits and the supply of petrol was extremely niggardly. Of course, this device was aimed at restricting the movement of the people. This affected the occupations and business of the people.

Press Censorship

From its very inception, this government has been suffering from a press-gag mania and had set its face against the freedom of press. But in the face of a spate of criticism both within and without, it had to veil its feelings for some time. These pent-up feelings however, broke out like a volcano and simultaneously with a declaration of a state of emergency and curfew in the Tamil provinces. The censorship of the press was imposed throughout the island.

In imposing the censorship of the press, the government had a two-fold purpose. Firstly, to avenge the criticism of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party during the time of the last general election by the press, and secondly, to shut out any possibility of exposing the government on account of its undemocratic and unjust acts affecting the liberties of the people of Ceylon, the private enterprises and more recently the acts of suppression of the freedoms and rights of the Tamil speaking people. A government that requires the press to clack its blunders and wickedness or in default seeks to gag it cannot claim to be the guardian of democracy. In fact it does just the opposite – it endangers democracy to a great degree.

The Daily Telegraph, commenting on the attitude of the Ceylon government to the press, on 27th October (Friday) 1961, observed as follows:

“The liberties of the people of Ceylon are in mortal danger…To convert an alleged private monopoly into an actual monopoly controlled by the state is, of course, to destroy the freedom of the press - root and branch.” [dots, as in the original]

The government is seeking to establish a Press Council, filling it with its own men to supervise and direct journalism in the manner it wants. Only on the license of the Press Council one can act as a journalist. Freedom of the press which has been recognized and honoured by governments of all ages, is now to be thrown in the gutters in this little island of Ceylon. It is not ‘a little totalitarianism’ but militant totalitarianism that is quite visible in the horizon of government politics in this country today. Unless the people shake out their timidity and their desire for self promotion and challenge the government’s unjust and undemocratic bent and halt it, the country will definitely be heading for autocracy or a major crisis. We must always endeavour to evolve an alert, vigorous and healthy public opinion which alone can provide the real pulsation of democracy. Commenting on the lack of public spirit in Ceylon, The Times of Ceylon, in its editorial of December 3rd 1961 observed as follows:

“Every country gets the government it deserves. Where public opinion is alert and vigorous, it automatically provides the checks and balances which keep a government on the rails of progress. Where, on the other hand, public opinion is timid or cowed, the government becomes autocratic and does what it likes, right or wrong. And that is pretty well the state of affairs in Ceylon today.”

The emergency, the curfew, the censorship of the press, the disorganization of the postal and telegraphic services and the cutting off of communications with the foreign countries during the curfew days had made it difficult for the outside world to take a peep into the affairs of Ceylon and in particular made the two Two provinces look like a prison house devoid of the light of freedom. The government had sought to shut out the sympathy of the world and deal with the Tamil speaking minority in the manner it wanted, persecute them and if necessary, destroy their entity. The entire situation reminds us of a wicked man kidnapping a fair young lady from her dearest kith and kin and confining her in an isolated and dark dungeon to ravage her, a helpless victim, in the manner he wants.

*****

Chapter 19: The Curfew, Military and People (pp.165-179)

It is only several hours after the military attack on the satyagrahis at 3 am on Tuesday 18th April that the people came to know that a state of emergency had been declared. After 9 am, the police announced through loudspeakers that curfew would commence at 12 noon on 18th April and that the people should get back home before that hour. This announcement also indicated that the curfew was limited to the municipal area of Jaffna. The author was himself present when the announcement was made. Only a few people, who heard it, knew about the curfew. The announcement was neither adequate nor timely so as to acquaint the people with the details of the curfew. Talks of curfew and military made the people panicky. Every one was anxious to get back home. People bound for distant places were nervously hastening to the bus stands where there were no buses. Suddenly there was a scramble for taxi cars. Cars and other vehicles began to move about at terrific speed. At every turn there was traffic jam.

Relying on the police announcement that the curfew would commence at 12 noon the city dwellers were still about the streets trying to learn more about the sudden developments. It was about 10.30 am when the author drove out of the city. But in one or two minutes the author saw the military attacking the people in the streets for ‘breaking’ the curfew. A cyclist who was going back home at a frantic speed was pushed violently by a soldier. The cyclist fell and rolled knocking his head against the road. The soldier then struck him on his head with his rifle-butt causing him a bleeding injury. The other soldiers too, who came in a truck engaged themselves in assaulting the pedestrians. Even children were not spared. A child was caught, intimidated and tossed about by a dark and rough soldier and as the child screamed aloud for help he dropped him violently on the ground. A woman advanced in pregnancy, was also chased and as she got on the steps of her house she almost tumbled, panting and heaving for breath. All this happened in a few moments.

I reversed my car and took another route. Having gone out of the municipal limits, I thought I was on safe ground where the curfew did not operate. It was a village committee area. To my utter surprise, I saw a soldier chasing a boy into a house. A few yards beyond that, I saw two soldiers stopping a car and trying to pull out the driver who appeared to beg for mercy. They got him to reverse the car and return the same way he had come. Before 12 noon, the alleged hour of curfew, many persons been mercilessly assaulted and injured by the military. The military made full use of their heavily-buckled belts and the rifle-butts to terrorise them into submission. It was clear that the police version and the military version about the commencement of the curfew contradicted each other. For this the innocent people had to suffer!

Suddenly, Jaffna a city of innocent activity and terrific din, changed into a desert of isolation! For two full days (18th and 19th April) curfew was to operate with a three hour break on 19th April, alleged to have been for the purpose of shopping. In effect, it was no break at all, for the majority of the people did not know the radio announcement. Even those who had known it could not leave their houses to pass on the information to neighbours. Not even 5 percent of the population went out for shopping. Where to go for shopping? Did the government, suddenly, hold a fare anywhere? Some of those who went out for shopping received flogging with belts by soldiers. Even the soldiers did not know of the break in the curfew! The announcement of the break was not at all effective. It reminded me of a boy who jingled his coins in his pockets about a hundred years away and then went back to his mother and said ‘Mother did you hear the jingling of the coins in my pockets?’

From 18th April till 6 am on Thursday 20th April, the people did not get out of their homes. Till then the electric lights, too could not be availed of and people had to live in darkness. It is after 6 am on 20th April when the curfew was partly lifted from 6 am each day, that the people came to know the developments. They learnt that the Federal Party members of parliament had been arrested and placed under detention at Maharagama. A number of active members of the Federal Party were also arrested and detained. The independent Member of Parliament for Vavuniya, Mr. T. Sivasithamparam was one of those detained. Mr. M. Sivasithamparam, MP for Udupiddy and a Member of the Tamil Congress, took an active part in the satyagraha movement and was in fact a member of the Action Committee. Some members of the Tamil Congress, too actively supported the satyagraha movement. But the government did not arrest or detain them! Certain Muslim MPs, whether of the Federal Party or not who led the satyagrahis in Batticaloa and Trincomalee on a number of occasions were also spared from arrest and detention. It became clear to the Tamil speaking people tha it was part of government’s plan to keep them divided and disunited.

The entire Northern and Eastern provinces mourned the arrest of the Tamil speaking Members of Parliament and the other leaders of the movement. On the day of their arrest, ie. 18th April, all shops and business establishments were closed and no work was transacted. The people spent the day quietly in prayer and fasting. They denied themselves the ordinary comforts and pleasures of life. The 18th day of every succeeding month was observed as a day of mourning and the traders, merchants, shop keepers and all others in the Northern and Eastern provinces staged hartal.

There was an incident at Valvettiturai. The government reported at first that ‘twelve satyagrahis’ attacked, on 18th April members of a military curfew enforcement patrol and that the patrol opened fire as a result of which three persons were injured. A few days later another report said: “They (army patrol) were set upon by a crowd”. These two reports contradicted each other and were far from the truth. On the spot information revealed that three soldiers had gone to Puluveddiankadu, place at Valvettiturai, and picked up trouble with two fishermen who were attending to their nets. These men having come back just then from se fishing, did not know that curfew was on and did not understand a syllable of the Sinhalese language the soldiers spoke. They spoke in Tamil which the soldiers did not understand. The soldiers intimidated them and attacked them. At once the two men threw their nets on them and trapped them. They attacked the soldiers with heavy instruments and two of them fell senseless. The third soldier managed to run away and whistled to his fellow soldiers who were in the next lane. They rushed to the spot and one of them shot at the two men who were then attempting to revive the two soldiers. As a result of the shot, both received injuries and were dispatched to the hospital. The reference to ‘twelve satyagrahis’ in the government report is incorrect as satyagraha was never performed at Valvettiturai. Following this incident a truck load of soldiers arrived from Jaffna town and set fire to a number of houses in that area.

There was another incident at Point Pedro. A government communiqué said:

“A curfew enforcement patrol in Point Pedro was attacked by a crowd with bottles, stones and missiles on the morning of April 19th (Wednesday). The vehicle in which the soldiers were travelling was obstructed by a hostile crowd on the road and the vehicle was forced to halt. The patrol party was compelled to open fire. The crowd dispersed. One person was found dead.”

This is totally distorted version of the incident. Here is the truth. It was curfew time. A person was walking along the road. Some soldiers shouted to him to stop. That man did not stop. Immediately a soldier opened fire. That man fell dead. This incident was witnessed by many persons from their own homes that were in close proximity to the place of the incident and as it was curfew time they could not go out. The identity of the deceased man revealed that he was a dumb and deaf person by the name of Velan Kidnan and a dhoby by profession. It was a cruel and thoughtless shooting! If there was a crowd as the government claimed, many others in that crowd would possibly have received injuries if the patrol party opened fire.

In both of these incidents the government referred to crowds and curfew enforcement patrol but common sense at least would not accept the report that there were crowds during curfew hours. That there were no crowds is not inferential but factual.

The Point Pedro magistrate Mr. .N. Rajadurai, a Tamil, who investigated into this alleged murder ordered the police to remand the soldier. But suddenly and with immediate effect, the magistrate was transferred to Kurunegala and thereby the government had prevented the Court of Justice from completing the preliminary investigations into this capital and heinous offence. And his transfer there was not even a talk of the preliminary inquiry into the alleged murder!

After this incident the government hurriedly gazette on Wednesday night (19th April), the same day the killing and inquiry took place, certain regulations which stated:

“In the case of any member of the police, Ceylon army, Royal Ceylon navy, or Royal Ceylon Air Force, a court which it would otherwise have been entitled to commit or remand such member to furnish bail or the fiscal, if such member is being detained in his custody in pursuance of an order made by a Court prior to the date of the coming into force of these regulations, shall upon production by an authorized officer of the appropriate certificate deliver him to such officer.”

The regulations contained several other particulars that gave to the government to deprive the Courts of Law of their normal functions thereby interfering with their administration of justice. This is not all. The government had attempted to get the emergency cases, in which military and police personnel were accused, transferred from the Courts of Jaffna to the Courts of Colombo with a view of rendering a full scale hearing impossible by causing hardships to witnesses who would have to travel 250 miles away from the places where the alleged offences were committed. This matter was referred to in the Senate by Senator S. Nadesan, QC, on Tuesday, 2nd May 1961. Mr. Nadesan in the course of his speech, observed:

“If the government for any reason thought that the judges in Jaffna could not be trusted to do justice in these cases, the obvious step was to have appointed other judges to their places and not to baulk inquiry and investigation by transferring cases 250 miles away from the place where the alleged offences have been committed.”

At Chavakachcheri, a lorry driver was asked by the military to remove the Tamil ‘Sri’ [number plate]. He was reluctant to do it. He was assaulted by a soldier while the other soldiers looked on. Under force, he removed the Tamil ‘Sri’. Then the same soldiers asked him to kneel down and worship the Sinhala ‘Sri’ [number plate]. The driver refused to do it. He was severely assaulted and kicked in the abdomen. Following this incident there was great tension at Chavakachcheri. The people opened fire and two army men were injured. One of them was the soldier who asked the driver to worship the Sinhala ‘Sri’. Later it was learnt this soldier succumbed to his injuries, but the government communiqué did not mention any such death. The military retaliated this on an innocent passerby whom they subjected to inhuman tortures. His screams and groans could be heard at a distance. He was set upon by a host of them. Limb by limb he was attacked; he was pulled, dragged and mauled and finally thrown away almost lifeless. They took him to be dead and left. After several days of unconsciousness, however, he revived and is still unable to attend to any work. Some soldiers of good families and breeding, it was understood, condemned their fellow soldiers for inflicting such heartless tortures on an innocent man.

At Valvetty, when a young boy was being assaulted by army men, a relation of his, one Apputhurai just peeped over the fence at the shouts he heard. It was about 5.45 pm and was not yet curfew time. Immediately the army men rushed into the premises where Apputhurai was standing and flogged him with belts and knocked him down with rifle butts. They then kicked him with booted legs on his chest and hips. He fell on the ground reeling with pain. He being the mainstay of the family which was in humble circumstances the family had to undergo great financial distress and take barely one meal a day as he was thrown out of work for many weeks.

At Tirunelvely, a boutique keeper was assaulted by a few soldiers while he was having his bath. They belted him heavily and as they pushed him down he knocked against the trough structure. As he got up, they again assaulted him. He cried for mercy. Later it was known that many a time these soldiers had deprived this boutique keeper of his cigarettes and beedies without giving money in return. On an earlier occasion, these soldiers asked for cigarettes and beedies and the poor shop keeper was a bit hesitant to give them. That was all the mistake he had made!

One Ramalingam was teaching his children in his house at Tirunelvely. The lights were on. The front door was locked. Issuing threats to him, some soldiers got him to open the door and then, thrashed him with belts, hands and rifle-butts and ordered the lights off. At Kalviankadu, army men threw stones at the portico light of a house belonging to a teacher named Rasiah.

At Vannarpannai, army men entered the house of one Sivakumaran Pasupathy, a Crown Counsel; he was preparing the prosecution case to be heard by the Assize Court at Jaffna. The soldiers insisted on his putting off the light. [Insert by Sachi: This probably refers to Siva Pasupathy, who became the Attorney General in 1970s, during Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s second tenure.] He, however pointed out to them that he was preparing the prosecution case to be heard by the Supreme Court the following day. But they would not listen to him and he had to switch off the light and go to bed. The following day he informed the Assize Judge what had happened the previous night and indicated that he was not ready to present the prosecution case. The murder case had to be postponed to another date. Throughout the whole of the Northern and Eastern provinces the army ordered the people to put off their lights. Any house that displayed prominent lights ran the risk of entry and ravage by soldiers. When this blackout was questioned and condemned in parliament by Opposition members, the leader of the House Mr. C.P. de Silva said – “An official (a soldier) had misunderstood the curfew for a blackout”!

At Tirunelvely junction, in the early hours of a morning the military, as if run amok, assaulted a number of men who were at the junction. They entered into houses and shops and flogged the inmates with belts and electric wires. Mr. Sinnappu, a proctor, was set upon by some soldiers while he was in his own house. He sustained injuries. A firewood depot watcher by the name of Kandavanam got the worst at his hands. Out of fear he hesitated to open the gate of the depot. The soldiers got over the gate and lashed him many times with electric wires. He yelled out in pain that was unbearable. They then kicked him in the abdomen with their booted legs, a practice to which they had become quite wont during those days of satyagraha and the curfew. He lay unconscious for a number of hours. Another person, one Kandiah also received the same cruel treatment. Due to flogging with electric wires their skin was peeled off at several places and they bled profusely. The reason the army gave for their wild behavior was that somebody had meddled with a street electric wire. But an electrical engineer contradicted the army version and said that the soldered portion of the wire had melted owing to the hot Sun and given way and had, thereby, interrupted the flow of electric currents.

Army men lavishly helped themselves at the expense of shop keepers and boutique keepers. They walked into shops and boutiques and availed of tins of cigarettes, bundles of beedies, bottles of sweets, chocolates, bunches of plantain [banana] fruits, cakes and other delicious edibles. At Kondavil, some soldiers comfortably lifted a sack of dhal and placed it in a military truck. When the dealer asked for money he was promptly answered, “Go, get the money from Mr. Chelvanayakam”. As the dealer stood puzzled and scratched his head, the soldiers drove away haughtily. To the retail dealer leading a hand to mouth life, this loss was too much to bear. Numerous shops were thus raided and looted. Some cultured army men seemed to have confessed that they were ashamed of their fellow soldiers who had raided and looted the shops.

At Karaiyoor, a soldier pushed down a cyclist violently and as he got up the cyclist stared at the soldier in protest and told him courageously that though he was a soldier, he should learn to treat men as human beings. As he said so, the soldier and his fellow soldiers who were with him caught him and flogged him with belts and sticks. They also smashed his bicycle.

Houses with distinctive appearance, houses shining with glass doors and windows became targets for stone throwing by the military. The houses of Mr. Chellappah, advocate, one Rajasooriyar, one Kanagasabapathy, Dr. Thamotheram Shakespeare and one Sivadas were stoned for several days. Mr. Sivadas was an artist. His house was constructed on the American pattern and no doubt it gave an artistic appearance. For two days his house was stoned. On the third day during curfew time at about 10:30 pm, a military jeep suddenly stopped. Its lights were put off. A soldier was seen going up to the glass windows of the house and knocking down the untouched portions with his rifle butt. The glass windows were completely smashed.

At Muththiraisanthai, Jaffna, on 8th May, a shop was completely burnt and gutted down. The roof and shutters of the shop were of zinc sheets. To ensure catching fire, a tire soaked in petrol was placed on the roof and set fire to. The fire broke out at 11 pm (curfew time). There were two persons sleeping inside, a salesman – one Kandiah and a boy of ten, a son of the proprietor of the shop. The proprietor was one Thiyagarajah of Nallur. As the flames swept above and the heat affected them, the inmates struggled and rushed out through the door and narrowly escaped death. On information received, the police came to the spot. At that time there was a military truck with some soldiers. As the police were making inquiries, two soldiers, as if on the swoop, came upon the salesman who had not recovered from the shock, seized him and placed him in the truck which at one started to move. On seeing this, the police drove in a jeep after the truck and asked the soldiers to stop and deliver the man to them. It was almost after an altercation that the soldiers were compelled to hand over the man to the police. The goods in that shop were burnt to ashes. The damage was estimated to the value of rupees 10,000/- There were numerous other similar instances.

The average Jaffna man, in keeping with the education and culture, may be said to be fairly tolerant and less susceptible to provocation. But when the military sought to interfere with his private and domestic life, he could not sit tight and watch ignominiously. At Kaithady, certain soldiers attempted to have an approach to women. This led to gunshots on both sides. It was learnt that a few soldiers received very serious injuries and later two of them died. But the army authorities did not seem to have reported anything of the kind. There was another incident at Alaveddy, close to a toddy tavern. Some soldiers attempted to rape a young girl of 16. But her father ran up to her, held her in his arms and shouted for help. A number of people collected there and the soldiers drove away quickly. As a sequel to this, that day in the evening, a shooting incident took place at the Tellipaalai-Pandaterripu road. It was widely believed that at least two soldiers died as a result of the shooting. At Navanthurai, a little beyond Jaffna town, a soldier abducted a woman from her house while the male members were away and brought her back and left her at the gate of her house twelve hours later during curfew time. For several days, the male members of the house and this woman tried to track the soldier, but it was understood that this soldier was taken away from this place.

At Koddadi, during curfew time, it was rumoured that some soldiers entered a house where there were two women. There was no male member. As they entered the house, the women shouted for help, but simultaneously the soldiers who were outside at the gate started singing baila at the top of their voice. On account of this, the women could not be heard by the neighbours who were by no means in close proximity. So that as the baila went on, a soldier raped the young woman as the aged mother’s entreaties and her shouts proved abortive.

A young man named Ramalingam from Tirunelvely, Jaffna went by train from Jaffna to Maho. At Maho, he and twenty other persons got into a van and proceeded to Batticaloa. When they all reached the limits of Batticaloa district, an army officer stopped them. He allowed them to proceed but they were followed by some men in a military vehicle. After a few miles the military vehicle overtook the civilian van and directed it to a road that led to a jungle. There the ‘soldiers’ ordered the passengers to get down. There were no lights, no houses and no trace of any human activity. The soldiers suddenly struck the helpless passengers with their belts, clubs and rifle butts. Then, they despoiled them of their purses, handbags, rings, wristlets, bags and packages. Young Ramalingam with only a few miles to Batticaloa had yet to return hom at Tirunelvely, penniless and with dirty clothes, having been robbed of his clothes, money and other belongings.

On Wednesday, May 3rd, some army men stood close to the Udupiddy junction. The roundabout signboard carried letters in English, Tamil and Sinhalese. The Sinhalese letters were found smeared with tar, an act not recently done, but during the days of anti-Sinhala ‘Sri’ campaign. Some teachers of the American Mission College happened to pass that way. The soldiers asked them to wipe off the tar on the Sinhalese letters. The teachers promptly protested and said that they were not responsible for the smearing. Not caring for the reasons, they pointed their bayonets at them, insisted on their wiping off the tar. Educated as they were, the teachers felt there was no use in resisting the blunt and irrational men with guns and bayonets! So they complied. The teachers, however made a complaint to the police that very noon. The soldiers, on hearing the complaint that same day at 7.30 pm drove to Udupiddy, got into the dormitory, pulled and dragged two teachers to the road and severely assaulted them. At once a telephone message was given to the Valvettiturai police who readily came to the spot and found the military still on the road in front of the College. On questioning by the police, the soldiers said that the teachers were breaking the curfew!